The First Mills

John Clark, who built the first mill in the village in 1688 and the first on the river in Newton, was born in Watertown October 13, 1641. His father, Hugh Clark, moved from Watertown to Roxbury where he died in 1693, and was probably in Newton as early as 1681. His son John settled in Muddy River (Brookline), but his father conveyed to him by deed 67 acres of land in East Parish (Newton Centre) in April, 1681, about which time the son probably moved from Muddy River to his new possession. This land was on the easterly side of the Dedham Road (Centre Street), adjoining and south of what afterwards became the Common in Newton Centre. John Clark died in 1695 at the age of 54. In his will he bequeathed to his two sons, John and William, “all his lands on the river towards the sawmill, the residue of his property to remain in the hands of the executor, to bring up his small children.” Eight acres of land on the river including the sawmill were appraised at 180 pounds. Clark’s purchase on the east side of the river was 10 or 15 years earlier than Cook’s purchase from the Indian, William Nahaton (Nehoiden), on the west side. This land was upstream of Hemlock Gorge.

The sawmill changed owners many times in the next few years and had several additions. In May 1708 John Clark Jr. conveyed to Nathaniel Parker one quarter part of the sawmill, stream rights and the dam and eel-weir acquired from the Indians as well as a half acre of land, all for the sum of twelve pounds. This included an open highway from the county road to the mill and eel-weir. Shortly after, William Clark conveyed to Nathaniel Longley one quarter part of the same. Thus John and William Clark, Nathaniel Parker and Nathaniel Longley became equal owners of the property to which they added in 1710 a grist mill and in 1715 a fulling mill. A fulling mill contains a mechanical device to thicken or shrink woolen cloths by the use of fuller’s earth and water, and by the same operation to extract any oily substances that may be in the wool.

In 1717 John Clark sold his quarter holdings in the mills to Nathaniel Parker. In 1720 William Parker conveyed to Noah Parker, Nathaniel’s son, his quarter share of the mills, eel-weirs, stream and dam rights for the sum of 95 pounds. That same year Nathaniel Longley sold his quarter ownership to Noah Parker. Also in 1720 Nathaniel Parker conveyed to his son, Noah, his half interest in the mills and other properties which were then valued at 150 pounds. Thus Noah Parker became sole owner of the mills. In 1725 he sold the fulling mill with one quarter acre of land to Samuel Stowell of Watertown for 120 pounds. Noah died in 1768. He had been a leading citizen of Upper Falls for nearly half a century, serving the town as selectman in 1716. His mills and possessions passed into the hands of his son and administrator, Thomas Parker. Mr. Parker was a prominent citizen of Upper Falls, serving as a selectman of the town of Newton and was a representative to the General Court for six years. As a member of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress he helped write the first state constitution in 1780. He was also well known as a churchman, and was one of the organizers of the First Baptist Church at Newton Centre in 1780.

For 10 years after his father’s death it proved impractical to operate the mills because of poor business conditions caused by the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. However, the shutting off of trade with England and the turn of good fortune that brought France alliance with the colonies encouraged new investments in local industry and started off a new era of prosperity in the community.

For some reason Thomas Parker decided to sell his mills and as the result of two sales, in 1778 and 1782, Simon Elliot, a wealthy tobacconist of Boston, acquired all of the property. This consisted of all the mills and about 35 acres of land including the dwelling house, barn, malthouse and various other structures for the sum of l,700 pounds. Following his first purchase in 1778 he added a snuff mill to these buildings. This was the first introduction of the name Elliot into the village, one that would make a considerable imprint on the community. We shall continue that story later in this chapter.

Second Generation Mills Downstream

This sale did not mean the end of Thomas Parker’s business association with the village. When he sold his property to Simon Elliot he reserved four acres of land below the Falls, a place known as Turtle Island. In 1721 he added to this by purchasing a small lot on the Needham (Wellesley) side of the river opposite this land. Later he sold this property to Jonathan Bixby, a blacksmith who had married his daughter. With the sale of this land, Parker reserved the right to erect fulling mills and a right-of-way privilege past his son-in-law’s new purchase.

Jonathan Bixby dug bog iron from the neighboring fields and swamps, and after constructing a dam built a rolling mill for the manufacture of scythes, an article desperately needed in predominantly rural Newton. In 1783 a new dam replaced the earlier one and a sawmill joined the rolling mill. This activity introduced industries to a second industrial site in Upper Falls, sharing the advantage of a 26 foot drop in the river’s flow through Hemlock Gorge. For the next century or so industrial development here would match that at the upper dam.

Mill bells ushering in the nineteenth century were also awakening the village to new opportunities and development. The little lane between the two mill sites, now bearing the dignified name of Proprietor’s Way, began to be dotted with mill houses, boarding houses and a few privately owned homes. This activity attracted outside industrialists, and in 1799 Bixby sold his property to the newly organized Newton Iron Works which rebuilt the rolling mill and commenced operations in the year 1800.

Rufus Ellis, one of the owners, superintended the construction and operation of the mill. He immediately became involved in a controversy with the town of Needham over the ownership of Turtle Island, disputing Needham’s prior claim to it. However, the General Court ruled in favor of Ellis and the following account is found in Clarke’s History of Needham.

“On June 2l, 1803 Turtle Island in the Charles and one quarter of a mile below the Upper Falls, so-called in said river, being the same island upon which the Newton Iron Works Company have erected their Manufactory, was taken from Needham and annexed to Newton – on petition of Rufus Ellis, the agent for the Newton Iron Works.”

Infrastructure Improvements and Expansion of Industry

By now both mill sites were geared for expansion. The new industrial age was just taking hold in the young nation and these enterprising industrialists were anxious to ride the first wave of its success. The Ellis and Elliot interests vied with each other to capture the new markets for their products which were springing up over the country. However, their rivalry was not so great that they did not recognize and mutually attempt to remedy the one major stumbling block to the development of their businesses. That was the urgent need for an adequate highway to move their goods to the nearby shipping port of Boston. There was no direct access to the city, only rambling and poorly-kept roads passing through the villages of Newton Centre and Newton Corner, connecting with the old post road to Boston.

However, the manufacturers’ plight evoked no sympathy from their Newton neighbors since there was no chance that farmers were going to “accommodate those factory people” by imposing additional taxes upon themselves in order to finance a road to be used mostly by the industrialists. They saw the industries as a threat because they were luring their hired hands and sons into their employ with promises of higher wages. But in fairness, one must add that despite their animosity, concern about the resultant increased taxes was legitimate. Still bearing the burden of the cost of the recent war, it is estimated that after 1780 the average Massachusetts farmer had to give up a third of his income to taxes. As a result, the problem was met, as it was in many communities in those early days, by construction of the toll road through Weston to be known as the Worcester Turnpike (see section, Streets, Bridges & Parks). The completion of this highway through Newton in 1808, which conveniently passed the doors of the Boylston Street enterprises, triggered the anticipated boom in business and placed the village on an equal competitive footing with other industries in the area.

Owners at both mill sites sprang into action. In 1809 Rufus Ellis erected a new factory on the south side of the pike for the manufacture of cut-nails. It imported raw material from Sweden and Russia and soon was producing 1,200 tons of nails as well as 2,000 tons of other iron products, much of which was sold in the south. There is some evidence that this factory may have been in production before 1809 as this Upper Falls news item appearing in the Newton Journal of February 5, 1881 under the headline “Ancient Documents” would seem to indicate:

“A family in this village have in their possession two patent papers, one granted to Jonathan Newell for an improved machine for cutting and heading nails, dated at Philadelphia, August 12, 1797, and signed by John Adams, President… The other was granted to Jonathan Ellis for the machine for cutting of any length and size, dated at Washington, DC, Feb. 10th, 1807 and signed by Thomas Jefferson, President, James Madison, Secretary of State….”

Nails and Cotton

Nail making was one of the more important industries that heralded in the Industrial Revolution, and many were the inventors in a number of eastern states who vied with each other in producing a time saving and economical machine for the manufacture of various sizes of nails. Most of the early nail factories were built in the period 1796-1810 in places such as Fairmont, near Philadelphia as well as Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and several locations in New York State. Massachusetts had its share with factories at Wareham, Weymouth, Bridgewater, Dover and Newton Upper Falls. Inventors of nail machines included Benjamin Cochrane, Ezekial Reed of Bridgewater, Jacob Perkins of Newburyport, Walter Hunt of New York, Jesse Reed (son of Ezekial), a Mr. Ripley, Thomas Odiorne of Milford, Seth Boyden of Foxboro (brother-in-law of Otis Pettee) and our own Upper Falls men mentioned in the above news item. Jonathan Newell and Jonathan Ellis could be considered pioneers in the industry when we note that the first invention by Jacob Perkins was perfected in 1790 and the first patent for nail-cutting machinery was granted to Joseph G. Pearson in 1794. At Upper Falls where the Newell and Ellis equipment was first used, the original machinery had been made by Odiorne, a type that was securely fastened to the tops and sides of heavy oak posts, each about a foot and a half square. These were replaced by the Reed machine with Mr. Ripley’s improvements.

After the turnpike bridged the river, in 1813 Rufus Ellis built a cotton mill of 3,000 spindle capacity on the Needham (Wellesley) side of the river. Ellis ran the mill until 1840 when he leased it to Milton H. Sanford of Medway who continued operating it as a cotton mill. After his lease expired and improvements such as putting in new waterwheels and flumes were made, it was leased in 1844 to Barney L. White who replaced the sheeting machines and continued the business for five years before turning it over to Salmon S. Hewlett who operated it until the factory and machinery were totally destroyed by fire on May 5, 1850. It was noted that on the whole, this factory had been a successful and profitable business enterprise. Although it was comparatively small, it was among the first cotton mills in the nation, having been built in the same year as the well-known Boston Mfg. Co. of Waltham. Many of the timbers used in its construction were purchased in Boston at auction, having been taken as part of a prize at sea during the War of 1812. One of the timbers forming the east sill of the factory was still in very good preservation in 1880, although two buildings had been burned over it. The second building we shall describe later.

In 1800 Rufus Ellis had been the sole owner of the rolling mill, but a corporation formed by him purchased the Newton Iron Works in 1821. Later a new company was organized on June 14, 1823 consisting of seven persons operating under the name of Newton Factories with Rufus Ellis as Agent. It is noted that this organization of the Newton Factories in 1823 seems to have been the answer to a strong bid for business leadership within the community by a new concern at the upstream site. However, by 1835 Rufus and David Ellis had become the sole owners of the property.

Not a great deal is known regarding the brothers. They were born in West Dedham, David on June 21, 1765 and Rufus on March 13, 1777. Both came to Upper Falls in 1799 and became involved in the Newton Iron Works. Rufus built his fine home (still standing) at 1235 Boylston Street, residing there until his death on July 2, 1859 at the age of 82. David is presumed to have remained in the village until his death on November 24, 1846 at the age of 81. Some Ellis heirs continued to reside in Upper Falls as merchants and in other occupations, while others left to become well known as Unitarian ministers.

The Elliots of Newton Upper Falls

You may recall, that Simon Elliot of Boston had purchased all of Thomas Parker’s holdings and had taken up residence in Newton, occupying the Noah Parker House. Over the next few years he removed or remodeled the sawmill, fulling and grist mills while adding three more snuff mills, a wire mill, screw factory, annealing house, blacksmith shop and another grist mill. The older Elliot was joined in these enterprises by his son so that instead of a team of brothers, as in the case of the Ellises, it was one of father and son, both bearing the first name of Simon. Actually there were three generations of Simon Elliots. The first, however, had no connection with Upper Falls. Simon Elliot I was born in 1712, and died in 1761 and had married Jane McHurd who died in 1757.

It was Simon II who had married Sarah Wilson and was the first to buy property here in 1778. Some further background on this Elliot is taken from George Gibb’s book, The Saco-Lowell Shops:

“In 1760 his house on King Street (later State Street) was consumed in the Great Fire, and he built a mansion on fashionable Federal Street. He later became the proprietor of four stores – three on Butler’s Row and one on State Street.”

We also learn from Mr. Gibb that Elliot had been the owner of warehouses on Long Wharf which were burned September 30, 1780. In addition to that land upon which his buildings were located, Elliot bought considerable land on both sides of the river around Upper Falls. Mr. Gibb states that at the time of his death in 1793 he left an estate valued at about 15,000 pounds. It is said that the business he carried on in Upper Falls in the manufacture of snuff and tobacco was the most extensive in that line in New England. Twenty mortars were used in crushing the tobacco leaf. Records show that this business gave employment to quite a number of workmen, which would seem to indicate that there were more than just six families residing in the village as alleged in the year 1800. It was from this family of snuff manufacturers that the name Elliot was applied to hall, factory and street in Newton Upper Falls and not, as many suppose, from Reverend John Eliot, the noted missionary to the Indians, whose name was a different spelling.

After the death of Simon Elliot II on January 25, 1793, it required almost two years to settle the estate. He had stores in Boston as well as property in Newton and other interests which had to be settled. When the estate was finally divided in December 1794, it is recorded that his widow, Sarah, son Simon Elliot III and daughter Sarah (Sally) shared almost $50,000, aside from the property settlement. Sally was married to Thomas Handasyd Perkins and his biographers state that she was the only daughter of Simon Elliot II. It is possible, however, that the biographers Carl Seabury and Stanley Paterson, (Merchant Prince of Boston, Colonel T. H. Perkins 1764-1854) and other reports might be error regarding the number of daughters of Simon Elliot II, because there is no mention made of another daughter, Margaret. Yet from Samuel Eliot Morison’s book, The Maritime History of Massachusetts, 1780-1860″ (p. 48) comes this footnote in reference to one Captain James Magee:

“Captain James Magee (1750-1861) described as ‘a convivial noblehearted Irishman’, during the Revolution commanded the man-o’-war brig, General Arnold, which was wrecked in Plymouth Bay. He married Margaret Elliot, sister of Mrs. Thomas Handasyd Perkins, and lived in the old Governor Shirley mansion at Roxbury.”

Simon Elliot’s son, Simon III, was known as General Elliot through his appointment as a Major General in the state militia in 1796. It was he who built a country home at Upper Falls including barns, cider mill and other farm buildings. (See story of Elliot family under “Biographies). At the turn of the century his Upper Falls property included all of the mill buildings mentioned earlier which were built by his father as well as the farm buildings mentioned above. Also included was a snuff mill and an interest in a paper mill at Lower Falls, previously owned by his father. In addition, in 1809 for the sum of $90 he acquired from Jonathan Bixby three ninth parts of Bixby’s undivided ninety parts of water rights to be used to turn one or more grindstones by water power at the iron mill. It is recorded that after 20 years of operation (1778 to 1798), General Elliot paid (under the U.S. excise laws enacted in 1798) taxes on a property valuation of $8,730.

By one criterion General Elliot was a rich man; he is recorded as owning one of only three horse-drawn carriages known to be in Newton at the turn of that century. There is no question he was one of the first capitalists in Newton, and it would seem at this point, that a successful business career lay before him. However, imprudent investments put him in a position where he was in need of ready cash. This followed a joint adventure he had with his sister’s husband Thomas Handasyd Perkins, when they both underwrote the cost of Boston’s first theatre, known as the Federal, in February, 1794. Now Eliot was in a position where he was forced to turn to his brother-in-law, Thomas Perkins, for financial help, and this resulted in Perkins, along with his brother James, advancing him $20,000 and taking over Elliot’s interest in the property at Newton Upper Falls. Thus Thomas Handasyd Perkins, the illustrious merchant prince of Boston, became connected with the mills at Upper Falls.

Thomas Perkins and the Upstream Mills

Thomas Perkins wife’s total inheritance from her father’s estate was considered a substantial one in those days and she turned it over to him for his handling. Thomas Perkins had been fortunate in that legacies had fallen twice to him in his lifetime. First it was an inheritance of 66 pounds, 13 shillings which came to him from his grandfather Peck’s estate when he reached age 21 and now, nine years later, his wife’s share of his father-in-law’s estate. As stated by his biographers, with normal prudence and care he need have no financial worries the rest of his life. Evidence that he did indeed exercise such caution is shown by the fact that when he died on January 11, 1854, he left a fortune of $l,600,000! (See his impressive biography in “Biographies” Section). So indirectly, our little mills at Upper Falls helped launch the career of a man whose achievements as an outstanding merchant dominates the pages of history of the formative years of the nation’s ‘s industry and commerce.

As previously stated, Thomas Perkins, in partnership with his brother James, had acquired from General Elliot in November, 1814 all of the mills and water rights together with 57 acres of land, tenement houses and farm buildings for the sum of $20,000. Their purpose was to build immediately a first class cotton factory of 6,000 spindle capacity for the making of sheetings. However, before they could act, Congress enacted tariff laws that had an adverse effect on this country’s manufacturers and resulted in opening the market to foreign competitors. The overwhelming influx of goods from abroad brought business almost to a halt at home. All of this resulted in the Messrs. Perkins postponing their factory enterprise until market conditions improved.

It would be seven years before there was enough improvement so that work could be resumed and they could expand their holdings. A company was formed in 1823 with $33,000 capital. Officers elected were Thomas H. Perkins, president; George H. Kuhn of Boston, treasurer; and Frederick Cabot, resident agent. Frederick Cabot was the great-grandson of John Cabot who came to this country from the British isle of Jersey in 1700 to ply his trade as a shipbuilder. Frederick Cabot’s position was assured by virtue of the fact that Samuel Cabot, who began his business career as a clerk in the firm of T. H. Perkins in 1800, had later married his employer’s daughter, Eliza. Their son, James Elliot Cabot, became a noted scholar and the official biographer of Ralph Waldo Emerson (a one-time Upper Falls resident), an honor which received the warm endorsement of the noted poet and philosopher before his death. The origin of the phrase, “The Lowells talk only to Cabots, and the Cabots talk only to God” is not known by this author. In any event, the new organization was called the Elliot Manufacturing Company by Perkins in honor of his wife, the former Sarah Elliot. After the formation of the new company in 1823 the Perkinses transferred 34 of the 57 original acres together with all the mills and other property to the new enterprise. They received $22,000 for the property which proved to be a good investment for the company.

This was the strong competitive organization faced by the downstream Ellis concern in 1823. Their answer, as previously stated, was to reorganize the corporation which had been solely owned and operated by Rufus Ellis since 1821 into the “Newton Factories”. Their two lines of business, cotton and iron, kept them busy for many years.

The Downstream Mills

In 1844 Frederick Barden leased the rolling and slitting mill property from the Messrs. Ellis and performed a thorough repair by building new and larger furnaces together with new and improved trains of rollers and new water-wheels and gearing. Through the use of an additional heating furnace he was prepared to manufacture at least 5,000 tons of iron annually and give employment to quite a number of workmen. He carried on a thriving business here for 25 years prior to his retreat in 1870. According to the census of 1865, 300,000 worth of iron passed through his rolling mill. However, after his retirement the mill remained idle for a few years, marking the end of a thriving business that had operated for almost three-quarters of a century.

In 1853, the building built in 1809 and operated as a nail factory was altered into a paper mill. This mill, on the south side of Boylston Street opposite the old rolling mill, was operated as a paper mill under a lease granted to Benjamin Newell of Dover in September, 1853. After a profitable business for 20 years making coarse paper Newell sold his interest to Hudson Keeney of Everett in 1873.

When the old nail factory had become a paper mill in 1853, the Ellis brothers built a new nail factory across the river on the site of the old cotton mill which had been destroyed by fire in 1850. The nail making machinery from the old factory was transferred to the new building, and the business continued for five or six more years before it was finally closed down and the machinery sold, thus terminating a nail making business that had given steady employment to its employees for more than 50 years.

Later, Charles Ellis operated a grist mill in the building, becoming a dealer in the sale of grain, meal and similar products. Still later, the firm of Webber & Cargill operated a planing and moulding mill on the premises until October 7, 1873 when a disastrous fire once again destroyed the building. It was never rebuilt.

In 1880 Hudson Keeney leased the now vacant old rolling mill and installed paper-making machinery which, combined with that in the old nail factory, doubled the capacity of his paper business. However, availing himself of a good opportunity to sell his interest in the mills, in 1882 he sold the business to Charles P. Clark, Jr. and William F. Wardwell. Unfortunately for Wardwell and Clark, the building was nearly destroyed by fire in November, 1888. However, they rebuilt it and continued to operate the mill for two more years before selling the business to the Superior Wax Paper Company. This company laid out thousands of dollars in preparation for making paper but ran into financial problems and was forced to close before beginning operations.

This merry-go-round appears to have stopped in 1890 when Willard Marcy of Upper Falls, his son-in-law, Eugene L. Crandall (acting as manager) and John M. Moore established the business of making wrapping and sheathing papers of good quality. With newer and improved machinery they could make about four tons a day in full operation. With the purchase of the Superior Wax Paper Company, Marcy and Crandall from Newton and Moore from Baldwinsville, Massachusetts acquired the real estate including the old nail factory and the entire interest in the water power of the Charles River, the reservoirs and the land adjoining. Mr. Marcy’s death, however, and Mr. Crandall’s acceptance of a better position in New Hampshire dissolved the company. Later it was taken over by the E. J. Hickey Paper Company and still later by the Rice Kendall Company in the name of Henry D Pope, a trustee.

The property was finally acquired by the Metropolitan Park Commission which must have razed these old buildings some time in the early 1900s, as maps dated 1895 show buildings on both sides of the river but on the next available map (1907) they have disappeared Thus, whatever remained of the original rolling mill built by Jonathan Bixby in about the year 1782 also left the industrial scene of the village.

Otis Pettee and the Elliot Mills

Returning to the Elliot Mfg. Company’s progress upstream, we find that in 1823 it had a very successful start due in part to one of its local officers. When the company was organized, the new directors employed Mr. Otis Pettee to superintend the mechanical department of their factory. This move by Mr. Pettee to Newton Upper Falls in 1823 was a permanent one although it was not his first employment in the village. In his book The Saco-Lowell Shops, Mr. Gibb tells us of an earlier appearance on the industrial scene here, (which is substantiated by other records).

“In 1819 or 1820, Otis Pettee accepted a call from Rufus Ellis to take charge of his cotton factory at Newton Upper Falls for the term of one year. After this one year he returned to Foxborough.”

Perhaps it would be well to pause here to include some of the great quantity of information available regarding the remarkable man who was to have considerable influence on the development of the village. Despite the colorful life of Thomas Perkins, coupled with the fact that he implanted the name of Elliot indelibly into the local scene, there is no question that without the influence of Otis Pettee upon this village, it would have reverted to an obscure hamlet after the departure of Mr. Perkins.

Before coming to Upper Falls, Pettee became involved in the budding textile industry when he established a small thread factory in his home town of Foxborough, Massachusetts. It is believed that this experience resulted in his summons to Newton Upper Falls to become Superintendent of the Ellis cotton mills and later Superintendent of the Elliot Mfg. Company – but not for the reason claimed in Seabury and Paterson’s biography of T. H. Perkins. Here they state that by the fall of 1807, the Perkins brothers, Thomas and James, organized a company called The Monkton Iron Company on Otter Creek in Vergennes, Vermont, and proceeded to hire technicians to operate the plant. It is recorded that “By January 1809, Otis Pettee, a refiner by trade, had been hired. He was the only experienced ironman on the place besides Bates (the foundrymate). If this is our same Otis Pettee of Foxborough, it is a remarkable tribute to this early genius since in 1809 he would have been but 14 years of age! it is possible that the Pettee to which they referred was one of Otis’s older brothers, Seneca or Joseph, who were recognized as experienced refiners in 1810 when they were operating a blest furnace in Salisbury, Connecticut producing merchantable iron. It was Otis’s brother Joseph who cast the anchor for the U.S.S. Constitution. On the other hand, if the Vermont story of the employment of Otis Pettee at Vergennes is true, his employment at Upper Falls by the Perkins brothers would have been the second engagement of his services by these men. It is strange that Seabury and Peterson in their book record his hiring in this fashion,

“As no one in the Perkins group had any technical competence in the textile business a local mechanic, Otis Pettee, was hired, since he was said to have had prior experience in the field.”

A further conflict in the recording of the early development of the mills is noted by items from two sources in reference to securing machinery for the new mills. Seabury and Paterson say,

“The next problem was equipment. Perkins was back from England in time to give his advice on this problem, which was to buy it from the people who knew how to make it – the Waltham concern. Perkins signed an agreement with them to build all (emphasis by author) the new machinery the Elliot company would require.”

Counteracting this is a statement by Otis Pettee’s son, Otis Jr., who, in 1884, wrote this in reference to the same period,

“The limited facilities for procuring machinery from shops already established caused considerable delay in the completion of their factory so the company decided that they would put up a large machine shop and build a portion of the machinery themselves, and with the addition of a brass foundry, they were enabled to make castings for the more delicate parts.”

He further writes,

“After the Elliot Company had completed the machinery for their own use they were prepared to build for other parties; in fact, they already had filled a few small orders from neighboring factories at Dedham, Waltham and other places. About this time the Jackson Company was building a large factory in Nashua, New Hampshire and entered into negotiations with the Elliot Company for machinery…”

Since Otis Pettee was to establish a reputation as one of the finest makers of cotton machinery in America, one is inclined to accept his son’s account as to what actually took place. In any event Otis, Jr. goes on to say,

“Early in the season of 1824 the hum of the spindle and the clashing of the loom testified to the outside world that they were in full operation, making thirty-six inch wide sheeting.”

Working Conditions

It might be of interest to know what kind of working conditions existed in factories of the early nineteenth century. Otis Pettee, Jr. quotes from a copy of an old poster “that occupied a conspicuous place in each department of a well-regulated manufactury.”

“Machinery will be put in motion at five o’clock in the morning from March 20th to September 20th, and all workmen or operatives are required to be in their places ready to commence work at that hour. A half-hour is allotted for breakfast – from half past six to seven. At twelve o’clock, three quarters of an hour is allotted for dinner, and at seven o’clock in the evening the days labor will end. From September 20th during the winter months, to March 20th, breakfast will be taken before commencing work, and the wheels will be started at early daylight on a clear morning; cloudy or dark mornings artificial light will be used; the dinner hour the same as in summer, the afternoon run will continue until half-past seven in the evening, with the exception that Saturday’s work will end with the daylight.”

Illumination in the beginning came from a lighted cotton wick in a can of oil. Later it was from tall, lantern type oil lamps with quarter inch thick chimneys. From another account by Otis Pettee, Jr.:

“Lighting up day in September would be ushered in with a kind of gloomy, funereal aspect by the workmen, while on the other hand, blowing-out time in March would be greeted with much joy and a deal of good humor. Frequently the old jacket-lamps would be sent hurtling through the workshops by some over-jubilant workmen, while others might be seen going out an open window or under a bench, and the day’s jubilee ended with a grand ‘blow-out’ ball in the old tavern hall or some convenient place, and kept up until the wee ‘sma’ hours of the morn.”

Gradually the number of work hours were reduced to twelve, to eleven and then ten, but labor in the farm fields had always been long and arduous, and the early manufacturers could not understand why men should not work equally as long indoors with machinery. Previous to 1840 the best mechanics or skilled workmen would command $1.50 per day, and, others a less price according to their rank as workmen. The apprentices usually received 50 cents a day for the first year, 75 cents the second year and $1.00 per day for the third year. There were no paid vacations, holidays or fringe benefits and, of course, no deductions unless (as in some early mills) there was a company store. In many ways the cost of living was less. Good board and lodging at regular lodging houses could be had for $2.00 per week for men and $1.50 per week for boys. The aim of many of the family men was to procure a small lot of land and build themselves a comfortable little home, and to cultivate a small garden patch for table use in its season. In many such ways a family could save a trifle here and there, and have a few dollars left from their yearly earnings to lay aside for support in their old age.

The foregoing is more or less the words of our earlier historian and we leave it to the reader to have his or her own thoughts about those “good old days.”

More on the Elliot Mills

Let us return to the history of the old mill. In 1824 there was a great demand for thread. The Elliot company had completed their Mill no. l and were putting in foundations for Mill no. 2. As previously mentioned, Mr. Pettee had manufactured thread in a small factory of his own in Foxborough and was therefore thoroughly familiar with the details of the business. The labor of building the required machinery was pressed forward to the utmost, and the next year the thread factory was doing a thriving business. No evidence exists as to the extent of Mr. Pettee’s income in the early days of the 1820s, but records show that he was not averse to doing a little moonlighting to augment his income. The year 1825 seems to be the one in which his diversified talents began to yield dividends. In the early days of cotton machine manufacturing many opportunities for the improvement of machinery were glaringly evident, especially in the area of “speeders” or roving machinery. Pettee’s keenly inventive mind quickly rose to the challenge with the result that he. had several patented processes in this field. The first one for the speeder bore the date March 15, 1825 for a “new and useful improvement for producing any required change in the velocity of machinery while in motion, etc.” This invention is considered to be one of the more significant improvements in the perfection of cotton machinery up to that time. Other improvements were covered by patents granted a few years later.

It was also during this time that the first post office in the village (the third in Newton) was established on May 30, 1825 with Otis Pettee serving as its first postmaster. Evidence of the need for and the uses for this moonlighting income is provided in this written reminiscence of one John Winslow who was growing up in the village at the time (this was during a later period when Mr. Pettee owned his own mills and other properties here),

“There was a good strong man in that time at the head of the Machine Shop and Cotton Mill enterprises whose name was Otis Pettee. He was a man of great energy, considerable inventive genius in mechanics, of exemplary character, and a most useful and honored citizen. Sometimes his enterprises were larger than his cash assets, and so, being the owner of the principal village store he would, when short of money, give an employee an order on his store…. As he owned most of the houses in which his workmen lived the rent account was adjusted in a “mutual way.”

These little side lines referred to earlier must have augmented his income, as tangible evidence still exists to show that as early as 1828 he was able to build a stately mansion on what was then known as Prospect Hill. Today, although somewhat altered it is an essential part of the Stone Institute, a fine institution and home for retired women. A picture of this imposing structure in its original state is included, from the Jackson Homestead’s pictorial booklet showing older homes in Newton Upper Falls. King’s Handbook (a history) of Newton in 1889 referred to it as “an antique yellow mansion crowned by a little spire and known as Sunnyside.” It was surrounded by a broad acreage of flowering trees and shrubs that swept down the gentle slopes to the distant river. As we shall learn later, it was his love for this beautiful home that helped him make an important decision only a few years after it was built.

As Mr. Pettee’s decision was to shape the destiny of the industrial future of the village, it might be well to complete the story of the Boylston Street enterprises that were slowly becoming part of the past. In 1888 the Newton Rubber Company, owned by Frederick R. Woodward, Sr. (a local business man who later organized the Stowe-Woodward Company) built a factory on the north side of Boylston Street next to what was then the Crandall Company paper mill, equipping it with the best modern machinery, it made a specialty of manufacturing springs for all kinds of machinery and insulating material for electric batteries, but it operated for only a short time when, either by merger or purchase, the company became the property of the International Tire Company specializing in the manufacture of bicycle tires. This resulted in quite a boom in business for a few years, but a consolidation caused the moving of the business and equipment to New Jersey. The building was later leased to the Leather Tire Goods Company and the Acme Broom Works. However, misfortune stalked these enterprises when on November 14, 1907 the building burned to the ground. It was such a spectacular fire that it is remembered by some of our oldest residents and how the heat was so intense that it was felt on the faces of onlookers as far away as High Street. The late Francis Jones of Cottage Hill recalled that many of the houses in the village caught fire from the flying embers, and remembered his father playing a garden hose over the wooden shingled roof of his house on Cottage Hill to save it from destruction – An exciting account of this fire appears later in this book. This fire removed the last building of the old industrial complex at the foot of Boylston Street.

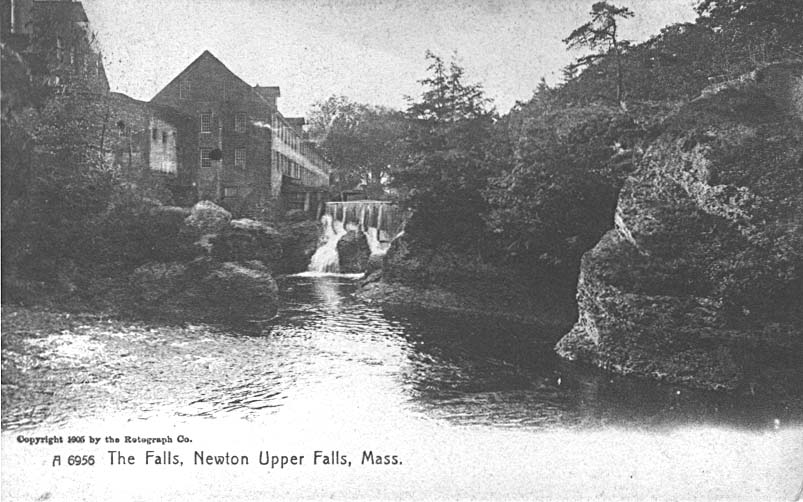

Much of the old waterway used to power the mills remained, however, with the water diverted from the river above the falls, channeled through gates and used by the mill before going under Boylston Street to be used by the mills on the other side. At one time the river divided above this point into what was known as the East and West Branches. The first dwelling houses in this area, with the exception of the Jonathan Bixby house, were built about the year 1800 to accommodate the workmen at the iron works established in 1799. While this and other evidence of the early industrial activity is still here, much is obliterated by the second widening of Boylston Street. When this road was built originally in 1808 its width at the river crossing was only about 30 feet, and the face of the dam was about 20 feet north of the bridge. [2006 addendum: The picture shows the upstream mill complex in 1905 or earlier, probably before construction of the “Horseshoe” Dam described below. Note the water level.]

In the first rebuilding and widening of the street, this old dam was removed and a new horseshoe type built in 1905 upstream on the southerly side of the new bridge, as we see it today. Built solely ‘to control the flow of the river, the dam was never used for commercial purposes’. According to Clarke’s History of Needham, the old bridge on the turnpike “at Ellis’s mills near the Cotton Factories” was a wooden structure on wooden piers until 1905, and the contractor who tore it down stated that “he thought that a portion of the timbers had been in this bridge for a century and a half.” It was noted that the old dam was also made of wood. The fact that there was once a ford in the river prior to any bridge is established by a further note in Clarke’s history, “In 1771 there was a fordway about half a mile north of Cook’s (Elliot Street) bridge.” Old maps show this location a short distance downstream of Turtle Island.

The Last Remaining Downstream Industrial Building: The “Stone Barn”

The stone building still standing on the south side of Worcester Street in Wellesley is the only remaining building of the original industrial complex on either side of the river. Some historians believe that it was erected either as an office building for the Newton Iron Works or as a storehouse for the nail and iron products produced in the factory erected across the street by Rufus Ellis in 1853. It is known to have been the meeting place and clubhouse of the Quinobequin Club when they had a golf course across the street before 1900, between the river and Chestnut Street. Mr. McLaughlin says it was later leased to James Easterbrook. Mr. Easterbrook first ran a carriage painting business near the corner of Cedar and Worcester Streets in Wellesley which he sold when he joined the Valentine Varnish Company of Boston. With this knowledge of the trade, he started a paint and varnish business in the old building and was very successful, partly because of some special formulas he created. Unfortunately, when he died in 1890 many of his paint mixing secrets died with him.

Eventually the stone building came into the possession of Henry Pope, trustee for the Rice Kendall Company, and as it was located on the Hemlock Gorge Reservation, it was acquired by the Metropolitan Park (District) Commission for the state in 1895. In recent years the building has been used to house some equipment operated by the Water Department of the Federal government for gauging the flow of water over the horseshoe dam. In the late 1980’s the Friends of Hemlock Gorge began the restoration of this building.

Similarly, in 1898 Mr. Pope granted to the Metropolitan Park Commission all his property on the northerly side of the turnpike in Newton for use as part of the Charles River Reservation. It appears that this same Commission later acquired the land on the south side of Ellis Street as far as the Baptist church property. There was one residence still standing on that side of Ellis Street next to Echo Bridge. It was formerly owned by Henry W. Fanning but was acquired by the Metropolitan District Commission as quarters for MDC police officers and their families. However, after standing vacant for some time it was set afire twice by vandals and the remains were finally razed.

We thus leave a section of the village that for 125 years played an exciting and important part in the industrial development of Newton Upper Falls. We will find as one reads the section, “The People,” that the owners and workmen in these mills left their mark on the gracious homes and cottages which still dot the hillside above the old mill sites. Even as one speeds by car today through this area on what is now Route 9, a vision of the old turnpike scenes when only stage and mail coach held sway is recalled by these ancient buildings. It was a complete community in those early days, containing one of the village’s earliest stores (1820s), a school (1818) and later its own church (1886). Regardless of its characterization by some as the “Lower place” (see Social Scene) it was definitely a contributing factor in the nation’s industrial beginning.

Otis Pettee’s Company

We now turn to the third significant industrial development in the village promoted, naturally, by the man who had participated in the development of the first two, Otis Pettee. One source indicates that about three years after he built his home here some differences developed between himself and the Elliot Mfg. Co. management which might have induced him in 1831 to leave the company and to strike out on his own . Seabury and Paterson in their book give the reason a different twist in this rather terse account:

“Otis Pettee operated the mill for the Perkinses until 1831. That year he left to open a textile machinery company…Perkins and his associates lent Pettee the money to get started on his on.”

That it might have been somewhat of a friendly parting as indicated by this account written later by Mr. Pettee’s son:

“In the year 1832 the Elliot Company discarded a large portion of their old machinery and replaced it with new and improved machinery…. A part of the new machinery was purchased in Paterson, New Jersey, and the balance of it from Mr. Pettee.”

However, it would seem that the loss of a man as versatile and inventive as Otis Pettee would have interested their competition in securing his services for any salary he would care to name. The records show that indeed this proved to be the case. Hardly had the news of Pettee’s departure become known when several concerns throughout New England sought his services þ However, for a reason many of today’s industrialists would not even consider, he decided to remain in Upper Falls and to establish his own company. His reply to their offers was a classic one:

“My home is here, my land is in a good state of cultivation, fruit trees are beginning to bear, flower gardens and green houses are in a flourishing condition and my family are comfortably situated. I see no reason why I cannot do as well here as anywhere else.”

It was a momentous and fortunate decision for the workers of Newton Upper Falls.

In 1831, on 12 acres of land purchased from Asa Williams for $1,200, he began the business of manufacturing machinery for use in the cotton industry. The plant was located on Mechanic Street below the present Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) tracks. He also acquired the water rights of South Meadow Brook which drained the Oak Hill meadows and flowed into the Charles River west of his property. His first shop was small but later he enlarged it until it was three stories in height and 365 feet in length. He also built a forge shop and in 1837 a foundry for making iron castings (the forerunner of one that was to be the largest in the east). He dug a reservoir at the rear of his plant, built dams and a water wheel for power, and in 1838 added steam power. It should be noted that while steam engines had been in operation since the early 1800s they were not yet in general use. As late as 1869 only 50% of industrial power was provided by steam. Surprisingly, we find that the Elliot Mfg. Company had to resort to steam power in 1836, since at that time water was diverted from the Charles River via Mother Brook at Dedham to feed certain manufacturing concerns in the area. The use of steam power naturally increased the cost of manufacturing. In this case, perhaps Pettee could afford its use in 1838. Despite a nationwide depression in 1837 which forced many of his competitors to shut down he had experienced a stroke of good fortune as his son was to recount later: “

“About the year 1825, Mr. Ithamer Whiting, a native of Dover (Mass.) left his home to seek his fortune in the gold and silver mines of Mexico. After leading a miner’s life for 10 years or more, he engaged in pioneer work for introducing the manufacture of cotton in that country… In the spring of 1837 Mr. Whiting came home to New England to procure the necessary machinery and fixtures for a cotton factory of sufficient capacity to produce about seven hundred and fifty yards of sheetings per day. After thoroughly canvassing the country Mr. Whiting finally gave the order to the late Mr. Otis Pettee, Sen., cotton machine builder in the village (Upper Falls). The contract simply called for machinery to produce seven hundred and fifty yards of sheetings per day, including all the necessary fixtures for the buildings etc., water wheel and mill work, doors, window frames and sashes, glass, etc., and all small tools necessary to operate and repair the machinery. Workmen skilled in the art of setting up the machinery and of operating the same were sent out to the factory for a term of three years or more, as educators to the Mexicans who were to be employed in the work. The machinery was completed in the fall of the same year (1837), and well boxed and shipped from Boston direct to Port San Blas, in a brig purchased by Mr. Whiting to be used by the mill-owners as a coaster, to gather up cotton from the neighboring ports, and as far south as Peru. About five years later, this company built another factory, for the manufacture of wraps to be sold in the country towns for the hand-weavers among the farmers, etc.”

Mr. Pettee goes on to say that for the next ten years the company made considerable profit on their venture but competition began to develop, as he continues:

“After the harvest this company was reaping became known to other capitalists in the republic, they at once became interested, and built other mills in different localities, and very naturally ordered their machinery from Newton.”

In reference to the first of these Mexican shipments we quote once more from Mr. Gibbs’ book:

“The machinery when finished, must be taken apart and packed securely in strong boxes to be shipped via Cape Horn and the Pacific Coast to San Blas; and as far as possible the gross weight of each package must not exceed 175 pounds for convenience for transportation on mules’ back from the port of entry to Tepic, a distance of about sixty miles. The Mexican orders constitute the earliest known exportation of any considerable amounts of American textile machinery and anticipate by more than half a century the next great exodus of such equipment.”

Indeed this is a definite indication of the genius of the remarkable Mr. Pettee.

But as quickly as good fortune had smiled on him in the years 1837 and 1838, as quickly did it frown. In the fall of 1839 a devastating fire leveled the largest of his machine shops, with an estimated loss of $100,000. However, with a boldness that characterized the man he not only rebuilt his plant the following year but, also in 1840, after becoming aware that stockholder disagreements were threatening the liquidation of the Elliot Mfg. Co., was able to acquire the property for $46,000. Of this sum, $38,000 was in the form of a mortgage held by the old owners, while the balance appears to have been paid cash. Pettee renamed the company the “Elliot Mills” and after some alterations brought them back to become a profitable company. At this time the demand for print cloths was sufficient to warrant changing machinery from the broad sheeting loom to the calico width, And at the same time enlarging the factory buildings and putting in additional machinery sufficient to nearly double the productive capacity of the mill. Two hundred fifty-two new looms were packed in a single room, and all driven from below instead of the usual method of belting down to them from lines of shafting overhead. This room was reputed to be the largest of its kind in New England, and when in full operation could weave 60,000 yards of cloth per week.

After his death his sons, Otis and George, formed a partnership with their brother-in-law, Henry Billings to continue the manufacture of cotton machinery. The new economy was named Otis Pettee & Company. They continued to do business together until 1880 when Billings bought out his three partners This ended the active participation of the Pettee family in the affairs of the company.

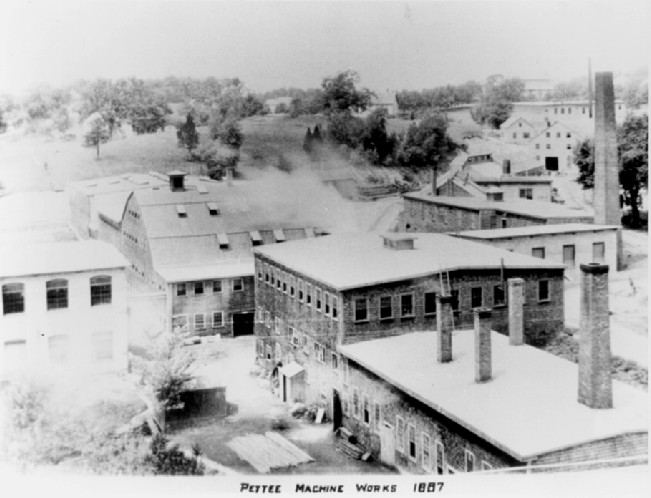

1882 Henry Billings organized the Pettee Machine Works with a capital of $200,000 of which $75,000 was for plant and equipment. However, Billings’ failing health limited him to only a few years of active participation in the management, although before his death in 1887 he built up an organization that lasted well into the twentieth century. Among some of his personnel was his son, Rodman Paul Billings, who graduated from Harvard in 1881 and became treasurer of the company. Later, during the period 1923 to 1932 he acted as Vice President. Mr. Billings had trained, as his successor Frank J. Hale, the son of a local farmer, Amos L. Hale. Frank Hale was General Agent from 1887 to 1923 and Vice President until 1932. Another well known local resident hired by Mr. Billings was Oscar Nutter (MIT ’87) as Assistant superintendent in charge of production including the duties of personnel management. Mr. Nutter held this position until 1917 and the office of Superintendent until 1922 when he became General Agent. He retired in 1932 but remained active in business. He entered into the management of his son’s surgical instrument company in Needham and remained there until the age of 91. He died in 1960 at the age of 96.

In the years between 1887 and 1905, the number of employees of the Saco & Pettee Shops (as it was later called) increased from 100 to more than 500, the foundry output from six tons to 80 tons per day and the monthly shipments from 32 units to 1,600 units. In 1895 a building program was started that included replacement of all the older shops and the building of a new foundry, one of the largest the east, embodying the latest design in construction and operation. In 1897 a merger was concluded with the Saco Water Power Machine Shops in Biddeford, Maine. A new company, the Saco & Pettee Machine Shops, was incorporated with $800,000 capital stock and the next 25 years were ones that brought prosperity to the company.

However, one transaction during this period was to have a detrimental effect upon the village later. This was a merger in 1912 with the Lowell Machine Shops and the Kitson Company of Lowell. Other weaknesses were also developing. The Lowell and Biddeford shops, because of their type of. product, were high expense, low profit units, and there was also some mismanagement. There was little new mill construction. As a direct result, the Kitson Shops and the Newton plant were closed and useable equipment. as well as personnel who were willing, were moved to Biddeford. This was in 1932, at the height of the Great Depression, and just about 100 years after the forming of the original company. Thus, the largest and most stable firm left the Village, leaving behind some bitterness and memories not yet completely erased from the minds of many in the community.

This left only one of the three original mill sites occupied by industry, the home of the original sawmill of 1688. After Otis Pettee died, the old mills on Elliot Street in 1853 were sold to a Boston company which continued to operate them under the name of the Newton Mills.

Newton Upper Falls in the Second Half of the 19th Century

At this point we might review how the village was faring almost 200 years after that first mill made its appearance. In 1850 the village boasted of having 1300 inhabitants which was 25% of the population of Newton. By 1866 there were 1,400 residents in Upper Falls (Newton Highlands became a separate village about 1865).

In 1866 there was a noticeable jump in the population of Newton as a whole to 9,100 persons, marking the beginning of the town’s role as a “bedroom” community. That year Newton Mills had 300 employees; Rolling Mills, 30-40, Otis Pettee & Co., 175, and the Locomotive & Repair Shop, 100. This was a war year and taxes were heavy as indicated by this newspaper item of October 13, 1866

“The heaviest tax payer among manufacturers is the Newton Mills at Upper Falls (cotton goods), from $1330 to $2710 month… Messrs. Otis Pettee and Co., pay a quarterly tax of from $1200 to $1500 upon machinery, etc. manufactured. The Rolling Mills at Upper Falls pay over $200.”

The Silk Industry in Newton

Let us continue our story of Upper Falls industry, particularly that of the Newton Mills. Ten years after Newton became a city, competition with larger companies brought so serious a decline in orders that the Newton Mills were driven out of business. It was closed in1884 and the property put up for sale. 170 employees, many of whom were of the second generation of families long associated with the mill, were without work. Several news items of the period reflect the concern of the village over the uncertainty of the mill’s future. What consternation must have been felt when this item appeared on July 19, 1884.

THE NEWTON MILLS TO SHUT DOWN INDEFINITELY

“The depressing news was made known last Wednesday morning that the managers of the Newton Mill had ordered this large and important manufactury to shut down for an indefinite period. The reason given us by the Superintendent is that the market is so dull and has been for the past six months or more that it has been found inadvisable to continue operations any longer. One hundred and seventy hands are employed and the gross monthly payroll is between three and four thousand dollars. The mill will close as soon as the stock is run out, which will be sometime in the latter part of August. The mills manufacture cotton prints entirely, and have been running about fifty years, and a large part of the help have resided here a long time and have families. They have never shut down before in all these years, and, therefore the present departure is looked upon on with more seriousness and apprehension by many than though an occasional stoppage had occurred.”

About a year later, however, this item appeared which seemed to be the bearer of better news. This was dated August 29, 1885:

PURCHASE OF NEWTON MILLS

“We are permitted to announce as a fact that Mr. R. T. Sullivan has purchased the Newton Mills buildings from the Newton Mills Corporation, and that soon he will be able to announce his intentions as to what he will do with them. This is welcome news to many in the village.”

This was followed by a further note or the same subject that appeared in the Newton Journal of September 12, 1885;

“As a result of a desire to encourage the starting up of a new industry at the Newton Mills by Mr. R. T. Sullivan, an order was adopted by the Board of Aldermen at their meeting last Monday providing that for the next ten years the valuation for a tax levy upon this property shall not exceed $50,000.”

Exactly what happened in the interim is not known, but an atlas of the city for the year 1886 shows the mills with the name Newton Silk Mills and the owners listed as Phipps & Train. The mill houses were in the name of the Newton Mills

Mr. Sullivan apparently never operated the mills for any purpose as further research reveals that on December 9, 1885 a silk manufacturing company, William T. Ryle & Co. of Paterson, New Jersey had purchased the property and rights to all production machinery for $40,000. That same year they gave a five year lease on these rights to Walter Phipps and Franklin Train of New Jersey who began the operation of spinning silk on April 24,1886 at the plant. A newspaper account of May l5, 1886 records this:

“The new company, which under the name of Wm. T. Ryle has purchased the old Newton Mill, have taken possession and are removing the old machinery, preparatory to the introduction of new, after which active operations will at once be commenced.”

Phipps & Train never purchased the property, renewing their lease at five year Intervals during the 34 years they occupied the buildings. They hired, 130 employees to operate machinery spinning silk warps for upholstery . Dress goods were also produced from waste imported from Asia. Business was so successful that night shifts were necessary to keep up with orders. In addition, there was the home activity of “picking” silk. Bundles of silk waste were taken to homes where mothers and older children picked out the colored threads. This was clean and easy work, though tedious, but in many families the income it provided was a welcome addition to the household budget.

The first attempt at silk culture in this country of which any record has been found was made in Virginia in 1623. In 1645 it was ordered by the colonial government that every planter should raise at least one mulberry tree for each and every ten acres of land they owned, or pay a fine of ten pounds of tobacco. A few years later the government of Virginia offered a bounty of 5,000 pounds of tobacco to any one who could produce 1,000 pounds of wound silk in a single year. However, this offer increased the production to a point where in 1666 the bounty was withdrawn, which in turn practically ended the silk culture as planters then turned their attention to more profitable crops.

Still, interest in silk manufacture revived in various places during the latter years of the colonial period. Major William Molineaux of Boston in 1770 became involved in its manufacture and in 1790 Ipswich, Massachusetts produced many articles made of silk.

Jesse Fewkes of Newton in 1822 had a small factory where he made a superior quality of fine lace and other products from silk fabric. Jonathan H. Cobb of Dedham in about 1830 had one of the most successful silk businesses in eastern New England. In 1857 his production amounted to $10,000 when the entire production of Massachusetts that same year yielded a value of $l50,000. Cobb was among the first to be interested in silk culture, giving considerable attention to growing the mulberry tree and the feeding of silkworms. The Morus Multicaulis, or Chinese Mulberry, was the most prolific in foliage and furnished a tender .leaf which was the favorite of the worm. However, our climate proved to be too cold to permit its economical culture. Still, there was quite an interest manifested by the agricultural community generally in regard to the propagation of the mulberry, and, the principal nurserymen of Newton tried growing the trees. Several large fields of the Chinese Mulberry were cultivated in the years 1838 to 1840, and thousands of silkworms were fed. Nevertheless it is said that beyond the reeling of small quantifies of silk from the cocoons nothing was done, and for the next ten or twelve years the culture and manufacture of silk in Newton waned. In 1832 Joseph W. Plimpton built a large ribbon factory in West Newton, and employed a number of skilled workmen in weaving a great variety of fancy ribbons and dress trimmings. In 1855 when the total value of the silk products produced in Massachusetts amounted to $750,000, Mr. Plimpton’s production had amounted to $38,000. In 1857 he sold his factory to his superintendent, Charles H. Garatt, who operated it but for a short time as it was destroyed by fire in 1859.

In the 1860s Isaac Farwell Jr. started a sewing silk factory at Newton Lower Falls and was quite successful. In 1870 he moved his business to Newton Corner near the Watertown line, but after operating there but a few years he moved, his business to Connecticut.

(Note: Much of the foregoing regarding silk culture and associated operations was taken from the History of Middlesex County, compiled by D. Hamilton Hurd, published by J.M. Lewis & Co., 1890″)

Closer to home, in Newton Upper Falls where Phipps & Traln were making the first switch from cotton manufacturing to working with silk, there had been several prior experiments in silk culture by William Kenrick, descendant of the earlier settler, John Kenrick. In the early days of the nineteenth century he planted a grove of mulberry trees to provide food for his silkworms and later wrote a book regarding his experiments called the “American Silk Growers Guide.” It has been thought that the large stone barn (so-called) on Oak Street was built for a nursery of silkworms and a place for the manufacture of silk, but Otis Pettee Jr., son of the barn’s builder and the source of much of the material in this chapter on Industry, says he does not remember his father ever revealing to anyone his purpose in building the structure.

During World War I, because of the stoppage of imports of silk from the Orient, the silk mill at Upper Falls practically shut down. In 1920 the entire property was purchased by the New England Spun Silk Co. of Watertown as a subsidiary plant for the spinning of silk thread from short staples, somewhat like cotton spinning. In the Orient the method of making silk thread was to soak the cocoons in warm water which killed the silk worm inside, then unravel the cocoons and wind the continuous thread on a reel. These reels were sent to silk spinning centers in this country, particularly Paterson, New Jersey, where the thread was cleaned and dyed before being woven or knitted into material. The cocoons received in Upper Falls were mainly those from which the silk worm, having been transformed into a moth, had broken through the cocoon to liberate itself. This ruptured the continuous thread leaving only broken filaments. These cocoons had to be treated with an acid and neutralized by ammonia in order to remove the residue of animal matter (the silkworm carcass, bits of mulberry leaves and other material). The broken threads were then separated and carded, and all remaining foreign matter removed by hand before the threads could be joined and spun into a single strand preparatory to being dyed and then woven or knitted. An excellent and more detailed account of the process using the complete cocoon was written in 1908 by Upper Falls native Mary E. Warren, then a senior at Newton High School. It is included at the conclusion of this chapter below; click here to go to it now.

The newly purchased plant was changed very little except for the addition of one new building. One internal addition, however, might be of interest. In 1876, in the city of Philadelphia, people were celebrating the Centennial by visiting the exposition being held there. It is recorded that four-fifths of the nation’s population viewed the exhibitions during the 169 days they were on display.

Three of the exhibits which drew the attention of the 10,000,000 spectators were Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, the first typewriter and the stupendous Corliss steam engine that supplied power for every power driven exhibit at the exposition. This 2,500 horsepower reciprocating steam engine was 39 feet tall with a 30 foot flywheel, and it was advertised that its tremendous power would be equal to any job in the world. It turned out that its future job was to supply the power to operate our old mills here at Newton Upper Falls! The late Thomas Frazier, former superintendent of the New England Spun Silk plant, said that when the mills were acquired by his company in 1920 the engine was still doing an admirable job. However, its use vas discontinued during the Depression of the 1930s since only a portion of the plant was in use. Smaller electric motors supplied the power for the few areas in operation at that time. The giant Corliss engine was eventually sold for junk.

The Silk Mill at the End of the 20th Century

At its production peak in 1929 the New England Spun Silk Company employed 520 persons. However, in the 1960s the popularity of silk products began to wane resulting in a decline in business. A switch to the handling of wool worsted material was also not successful and the work force dwindled to 100 persons. The company turned to the selling of some of its property, particularly buildings known as the “silk mill houses.” It is believed that, dating from the organization of the Elliot Manufacturing Company in 1823, these houses and tenements had been occupied at a very low rent by employees only. However, near the end of the silk companies ownership they were offered to the public at large, although the buildings were old and without modern conveniences. After some extensive repairs, painting, electrical conversions and alterations, they were sold to the firm of Homes, Inc. A short time later, in 1962, the entire complex bounded by the Charles River, Elliot and Chestnut Streets as well as by the Baptist Church property in the north was sold to the Godino Company of Newton which held it for a few years before it was acquired by the G. Arnold Haynes Corporation. The Haynes Corporation razed all the mill houses inside the area mentioned above, converting it into a parking lot. Included was the house formerly rented by Edward Cahill where the first Catholic Mass was celebrated in Newton.

Very few changes have been made to the old mills themselves except for the removal of some of the transoms and dormers in the roofs. However the whir of wheels and pulleys and the slap of belts have been stilled. The old buildings were made into an office complex bearing the name “Echo Bridge Park”, the same name which was given to the recreational area once located on the banks of the Charles just beyond the factories, over a century before. Some buildings have been leased by various small businesses and stores, including a rare book store, and a restaurant through whose windows may be viewed the site of the ancient Indian eel-weirs, the picturesque Hemlock Gorge and the graceful arches of Echo Bridge. These areas, floodlit at night, give a picture postcard effect to this historical landmark. The old red-brick buildings now painted white, with an inner courtyard high-lighted at night by post lamps produce a very charming colonial effect that is a fitting tribute to these buildings, their owners and the thousands of workers who have contributed so much over the centuries to the prosperity of the village of Newton Upper Falls.

Other Industry

Until this point we have given our attention to the industrial development of the mills and factories which occupied the three ma]or mill sites in the village. Over the three centuries of industrial activity here there were, of course, many other manufacturing plants, large and small which played an important part in supplying a means of livelihood for thousands of other residents of the community.

Forges

There were a number of one man businesses including blacksmith and machine shops in the village of which there is little record. From various sources we do find the following:

“In 1807 Mr. Zilba Bridges moved from Holliston to Newton Lower Falls, purchased two acres of land with a forge shop thereon. A few years later he purchased a few acres of land upon the top of a hill near the Newton Factories at the Upper Falls and built a brick dwelling house and a frame forge shop on the premises where he conducted business for over twenty years. He had twin sons who later with sons of a neighbor Mr. Joseph Davenport formed a business for building railroad cars in Cambridgeport and Fitchburg under the name of Davenport & Bridges. They made considerable improvements in the existing railway cars building the first eight wheel car, etc., becoming quite famous in the pioneer days of railroading.”

While the location of Mr. Bridge’s residence is not known exactly, it is known that his neighbor, Mr. Joseph Davenport lived just above the present 965 Chestnut Street until his home was destroyed by fire in August, 1843. It is also known that Mr. Davenport moved with his family to Cambridge following the fire, and it is presumed that Mr. Bridges moved to that city at the same time.

Fires Often Destroyed Businesses

It is only through newspaper accounts of the many fires that occurred in the village that we get a record of the various enterprises that flourished (at least for a brief time) in the early days of our community, such as this article which appeared in the Newton Journal of August 7, 1869;

FIRE AT THE UPPER FALLS

“At two o’clock on Saturday morning last, a building on High Street, Newton Upper Falls, owned by Mr. Collin Cady, and occupied by Mr. Hosea C. Hoyt, for the manufacture of spring beds, was totally destroyed by fire with its contents, supposed to be the work of an incendiary. Mr. D. Johnson, shoemaker, and Mr. Buttrick, painter, also occupied the building and lost stock to a small amount. Mr. Wm. P. Smith, carpenter, in the employ of Mr. Hoyt lost all his tools.”

The location of this ill-fated small business is believed to have been on the southwest corner of High and Winter streets.

Bicycles and Machinery

A small machine shop was located on the property of Lewis Hurd on Boylston Street near the present Lucille Place. A similar shop was built by William E. Clarke in the rear of his home at 1185 Boylston Street, The shop was later moved down and across the street where it was made into a dwelling. In the early 1800s Pliny Bosworth built a machine shop on High Street where he and Clarke manufactured cotton machinery for a few years before going out of business. In 1849 two young entrepreneurs, Jenkins and Inman by name, started a braided shoe string factory on a small scale in a single leased room in a local factory building. The enterprise, at first a purely experimental one, proved to be a success. However, because of the lack of additional room to accommodate their expanding business, in 1852 they moved to larger quarters in Carver, Massachusetts where their company became the largest shoe string and lacing factory in the country.

In the late 1800s a local industry was engaged in the manufacture of bicycles, first the “high wheel” and later the “safety” or present type. H. H. Hodgson (later the Hodgson Brothers) in their shop on High Street successfully improved the high wheel type as indicated this news item of February 28, 1880:

“R. H. Hodgson at his shop or High Street, has on hand more orders for his famous bicycle, “The Newton Champion,” than he can possibly fill at present, and hardly a mail arrives without bringing in its contents an order for one of these ‘big wheels’.”

It is believed that whatever patents they may have had were sold to the Pope Manufacturing Company of Boston, later the Pope Hartford Company of Hartford, Connecticut, makers of the Columbia bicycle and the pioneer Pope automobile. Also, at the Pettee Machine Works there was some activity in the assembly and painting of high wheel bicycles. It is thought that this business was purchased by the Metz Company of Waltham which later made automobiles. The author feels that the Pettee Machine Works also were involved with the handling or manufacture of the present type of bicycle, as he owned in his youth a very lightweight frame bike bearing the nameplate “Echo Bridge” and presumably made by this company. It is recalled that these bicycles were very much in demand by the professional bicycle racers who performed at the Revere, Massachusetts track. An Upper Falls a news item appearing in the TOWN CRIER of August 26, 1910 confirms the location of this bicycle shop: “A one-story addition is being made to the bicycle shop on Oak St.”

It would appear from the number of shops that sprang up along High Street during the latter half of the nineteenth century that this street was destined to become the second “main street” of the village, paralleling Chestnut Street in importance. However, competition from other areas and the growing mobility of the people through the use of street car and automobile stifled this development, and slowly it reverted to the residential street it is today.

Printing

Before we leave this area we must recall one more business on High Street, the Fanning Printing Company, a long-lived and flourishing business run by a highly esteemed family who are still remembered by some of the older members of the community. They also had other business enterprises in the village including a grocery and photography shop.

Straw

In addition, for a little while, Upper Falls had some “straw men” who conducted the Newton Straw Works on Oak Street (near the depot) known as Cady & Hanaford Straw Shop, also as L.B. Hanaford & Co. and later perhaps since only as a memory since an old time record shows that Cady & Hanaford’s straw shop burned on December 7, 1868. Such companies as these are listed among the familiar shop and businesses which bloomed briefly and then were gone, including one which advertised in 1883 that “William Lowe will soon commence the manufacture of paper bags at his recently equipped factory near his residence on Chestnut Street.”

Around the perimeter of the village of Newton Upper Falls were many glue factories, mostly located on farms. To the north on the estate of F.A. Collins were two such factories as well as a sawmill and another glue factory on the estate of E.J. Collins. Woodward & Sons also operated a glue factory not far from their farm.

Fire Alarms

Other substantial and nationally known industries were clustered around the depot area in the latter half of the nineteenth century, and were important assets to the community. Among them was the Gamewell Fire Alarm & Telegraph Company. The nature of its manufacture at its beginning is found in this story appearing in the Boston Sunday Globe December 31, 1989: