Reflections

Chances are you have never visited Hemlock Gorge and walked its near-silent trails. Disturbed only by the melodic welcome of its feathered inhabitants. Alone, yet with an eerie feeling of another’s presence. You look down and see but your own tread etched in the sands of your pathway, almost expecting to see another shaped by the moccasined foot of one who once made this path his own.

And chances are you have never heard within the wild notes of the turbulent river below (as it rushes away to the nearby sea) the measured notes of an ancient counter melody echoing the last haunting cry of a dwindling tribe.

And chances are you have never trod the ‘deck’ of the massive seven-arched Echo Bridge and looked down, with your mind’s eye, upon a field dotted with wigwams. Never in the clear, cool air that frequents only these heights, breathed the nostalgic odor of the smoke of the natives ancient fires.

And chances are if you stood beneath the bridge’s soaring arch that spans the river, you might hear behind the echoing sounds of your own voice the soft whisper of those guardian spirits who were left behind to watch over their beloved gorge.

A place they left for your keeping.

Our walking tour of Hemlock Gorge begins

Roxbury Puddingstone and the Upper Falls Pot Hole

It is a rare time indeed when we can view an exquisite creation by Mother Nature born over 10,000 years ago, and then discover but a few yards away, its birthplace. From the intersection of Chestnut and Elliot Streets in Newton Upper Falls one can walk but a few hundred feet in an easterly direction on Elliot Street to a narrow gravel lane leading off the left side of the road, called Sullivan Avenue. About 75 feet from Elliot Street is a bulky ledge of ‘Roxbury Pudding- stone’ (composed of mixed lava and loose stone believed to have been spewed out of an ancient volcano somewhere in the Roxbury area). Facing the ledge one will note, cut into this rocky mass, a vertical smooth rounding scar, shaped very much like one half of a hole made by some huge boring tool. It is known as the ‘UPPER FALLS POTHOLE’.

Geologists tell us that 10 to 12 thousand years ago a huge glacier that had inched its way southward as far as Long Island Sound was halted by a warming of the climate. This forced it to retreat northward. As the bulk of this mass passed over the rocky height now called Prospect Hill in Upper Falls, it is said that its awesome facade loomed nearly a mile above the ledge upon which it rested. Melting ice and snow cascading down its face smashed into the rocky mass below. A granite-like boulder, lying in a pocket on top of the ledge, was caught in the glacial downpour causing it to rotate within its cavity. Acting like an auger or drill, it bored its way through the yielding ledge and later when the deluge tore away half the hole, it left behind the other smooth half, exposed as we see it today. The glacial floods reaching lower ground continued to tear their way through the softer earth and rocky ground as they sought the nearby sea. Some time later when a meandering river sought this selfsame sea it took advantage of the open gorge we now know as Hemlock Gorge, rapidly dropping 26 feet in the few hundred feet of it. length. In all of the 79 miles the Charles River wanders to reach Boston Harbor, this gorge represents the greatest drop in the river bed. Let us choose as a starting place for our tour the slight rise at the end of the open field that borders Central Avenue in Needham, just before the highway crosses the ancient Cook Bridge into Newton and becomes Elliot Street.

We Meet The First Inhabitants

If our imagination is working, perhaps we can ‘see’ and ‘hear’ the milling tribe of Punkapoag Indians that once gathered along the banks of the river a few yards away. They were a friendly people, part of an Algonquian Tribe led by a chief called by the English, William Nahaton (also known as Nehoiden and Hahaton). It is recorded that there were about “20,000 Indians [in the vicinity] at that time, [members of the] different tribes then in New England” And, “In 1657 the town of Dorchester granted to the Indians residing among them 6,000 acres of land at Punkapoag”. Most of them moved there. This was in the Blue Hill area and they were the tribe that found the gorge to be an ideal fishing ground. This land is not believed to be at that time ‘owned’ by the Indians. (More about this later).

North of the 15 foot high natural dam, a short distance downstream where the water level control dam is located the river teemed with fresh water species of fish. It is said salt water fish such as shad, herring and salmon often made their way upstream in the tidal waters that reached as far as the upper dam, in their search for a spawning place. Unable to leap over the dam they become a target for the spears of the Indians cast from the high bank below the dam. A deposition was made by some residents in 1790 who said they thought “in our Opinion that it was impractical for the fish to Assend said falls ever while wee consider it in the State of Nature.”

From the river bank at about the middle of the field below us, they built a flat topped wall across the river beneath the surface of the water. The squaws stood upon this wall holding a net of woven reeds for the purpose of netting fish as explained by Mildred Barney Talmadge of Needham in her STORY OF OUR TOWN:

“…the river was a source of food for the Indians. It is known that they had a fish weir at the Upper Falls. It is thought that they cut large branches of saplings and trimmed off the lower branches leaving the upper ones, making something not unlike a big broom. There would be several canoes with an Indian in the bow of each, holding one of these big brushes. With an Indian paddling each canoe they would start way up the river and drop the brush end of these poles well into the water, Then they would paddle down- stream sweeping the fish before them. At a narrow place in the river above the Upper Falls the squaws would be ready with nets woven out of reeds. The fish would be driven into them and dragged up on the bank. There the Indians would build fires, smoke the fish and lay them away in a cave to be eaten in the winter.”

And here is more information from KING’S HANDBOOK OF NEWTON, concerning these weirs:

“The Indians had their weir here near the great mid-stream rock below the Elliot Street (Cook) bridge and esteemed this commerce so highly , that they carefully reserved a part of the Needham shore to dry their fish upon. Although the tribe is extinct, this right is still legally intact, and every transfer of land in this tract must ‘ contain a clause specifying that the Indians may use the land for drying their fish upon…”

Contact with the white man began with greater frequency in the early seventeenth century. After Watertown was settled in 1630, settlers began to explore further up the river seeking out home sites suitable for farming, etc. There is a story that a group pushing their way up the river by boat in 1636 were terrified by the rushing waters of the gorge, darkened by the hemlocks, etc.

The ‘savages’ lurking in the shadows also discouraged them, and they continued up the river until they came upon the open meadows of a place they would call Dedham, which they settled in 1636. The same year the General Court granted these new proprietors of Dedham land on the west side of the river in what is now Needham, Natick, and part of Sherburne (Sherborn). This act, in 1680, allowed Dedham to negotiate with Nehoiden, the Indian chief residing here. Nehoiden received a large amount of land along the west side of the river to a point on the west bank downstream of today’s Route 9, on what was the Needham side of the river. (He also got ten pounds in money and 40 shillings worth of Indian corn). In exchange the chief gave them a tract of land he owned in an area now in the township of Deerfield, Massachusetts. This land measured seven miles long from east to west and five miles wide. The same year Dedham gave Naugus (also a chief) eight pounds for land he owned down river at a place called Maugus Hill, (believed to be in the vicinity of the so- called ‘Devil’s Den’).

However, Nahaton (or Nehoiden) sold his land as we note from a record of January (29), 1701: “William Nahaton, an Indian, of Punkapoag, for twelve pounds, conveyed to Robert Cook of Dorchester, horn breaker, forty acres of land on the west side of the Charles River, just above the Upper Falls, one hundred and twenty rods long and fifty-three rods wide.” (The nature of the occupation of ‘horn breaker’ is unknown). Regarding the land, historian Jackson says; “this is the same land which the inhabitants of Dedham conveyed to William Nehoiden (Nahaton) in April 1680.”

Clark’s HISTORY OF NEEDHAM supplies this information regarding Robert Cook:

“Cook was born in Boston (Dorchester) and his father’s name was also Robert. The younger Robert, later acquiring the military title of Captain, was considered one of the most prominent citizens of Dedham and later of Needham when it became an independent town in 1711. He was a surveyor of highways in Dedham in 1706, a constable in 1709 and elected a selectman in 1710.”

The purchase in 1701 of the land in the area by Robert Cook is the reason that the nearby bridge bears his name (as does a nearby housing development). We might also note that the land on the east side of the river was granted, also in the year 1636, to the proprietors of New Town (later Cambridge) by the General Court. In 1688, when New Cambridge (Newton) was established the first mill on the river in the new village (across from where we are standing) was built by John Clark although this first purchase of land by John Clark does net, appear upon the public records.

The Red Man Looks Toward the Sunset

While the relationship between John Clark and his neighbors across the river was cordial, this period marked the beginning of the gradual decline of the Indian influence in the area. Those who admired the river for its beauty and the bounty it possessed were being slowly replaced by those who used it for their monetary gain. The King Philip’s War of 1675-76 may have initiated the decline despite the absence of any indication that any animosity existed between the local Indians and our early settlers. But at this point, we sense it was the end of one era and the beginning of another. John Clark’s purchase in 1688, closely followed in 1701 by Robert Cook’s acquisition of land in and around the gorge, marks the beginning of the settlement of the area by the English and other Europeans. Near where we were standing at the start of our tour was once located a livery stable, run at one point by a man named McIntosh. Close by, located directly on Central Avenue was a house (owner unknown) which we will let a one time tenant, Adam Temperley, (whom this writer knew) describe. She had just arrived, at ten years of age, with her parents from England. This would be her first home in America, The year was 1874 and we quote from her journal:

“At last we reached Newton Upper Falls. We stopped at the first house after we crossed the river to the Needham side. It looked quite attractive on the outside. It was a double house, painted white with a white fence all around it and through the middle of the back yard, separating the two houses. There were two fine elm trees in front of the house, one on each side of the yard, with a fairly good sized plot of grass for us to pay on. One side ran down to the bank of the Charles river, so we had a basement kitchen on the east side, while the front of the hourse on the south was on a level with Elliot Street (Central Avenue) next to the bridge. We had five rooms, two on the first floor, three on the second, plus the basement kitchen facing on a small yard with the river for a boundary.”

Evidently Miss Temperley, writing the story of her life after her retirement did not recall that this home scee forty years earlier had been the location for a supposed murder of an infant, resulting in the appearance of a child’s ghost that caused an uproar in the village. The story begins with an account by M.F. Sweetser in his KING’S HANDBOOK OF NEWTON (Moses King Corporation. 1889). We quote from his book:

“On this bridge (Cook Bridge) fifty years ago (1839) the credulous countryfolk used to gather to watch for the ‘Baby Ghost’, a wee spectre whom they thought ran at times across the blue waters, while the rocking of its cradle could be heard beneath the stream.”

Sweetser goes on to say that the busy life of latter days had effaced the memory of this legend and its mysterious origin. However in the preparation for the writing of our book, MAKERS OF THE MOLD we were able to solve the mystery when we ran across the story of this ‘ghost’ in a news item appearing in 1882:

“In a letter received last week from an elderly gentleman, now a resident of Worcester, but a native of Lower Falls, he alluded to the fact of moving to Upper Falls when nine years of age, where he spent his youth, and dwelt with pleasure upon his recollections of many incidents of his life while there. He writes:”

“I have vivid recollections of the “Haunted House.” It stood near Charles River, and I recall the stories of a child having been murdered within its walls, and of noises and rocking of cradles heard nights, disturbing the slumbers of its occupants. And also the tales about a ‘baby ghost’ which appeared on a rock in the river opposite the haunted house. It was naked, and would rapidly pass back and forth from the rock to the water for an hour, and then disappear for the day. The ghost was about as large as a ten-months-old child. Hundreds went daily to what was then called Needham Bridge, to watch it. All could see it pass back and forth from the rock to the water; no one saw it go away, but it always disappeared. The excitement for a week was fearful. Every one seemed seemed to feel there was a connection between the baby ghost and the child of the haunted house. At this time I was twelve years of age. During the week, mothers would find their boys after dark, as they were afraid to remain out. After a few days a young man went to the rock to investigate, captured the ghost, and brought it to the crowd for inspection. It was found to be a piece of glass. The glass probably, hod been carried to the rock and left there at high water, and the sun, when it got to the right elevation, would shine upon the glass, and the agitation of the water as ti struck the base of the rock being reflected in the glass, produced the appearance of a ‘baby ghost.’”

Before we move on, look to the east straight across the river in the direction of the intersection where the traffic signals are located. On the northeast corner of the intersection is an eighteenth century farmhouse moved there almost two centuries ago. Between it and the first house on Chestnut Street you will note an opening, framing what appears to be a narrow lane. This is, or was, an actual highway laid out in 1688 “from the meeting-house (in what is now Newton Centre) to the Falls”. Jointly financed by the parent village of Cambridge and the new village of New Cambridge (Newton). This was covered by the first transaction between the newly separated villages, a copy of which may be found in historian S.F. Smith’s book, HISTORY OF NEWTON. The highway became part of the mill property on the river in 1688 and ceased to be a public way in 1714 when the Robert Cook Bridge and Elliot Street were constructed. Later when various transactions involving the sale of mill property were made, the old highway was included as part of the property and houses now located along its course are aware that it must be kept ‘open.’ For a brief period between its construction in 1688 and the year 1714, before Elliot Street crossed the river on the new bridge, the old highway continued beyond the mills, crossing the river at a shallow stretch of the river called a ‘fordway.’ The road then continued through the field we are standing on to join up with Central Avenue. Evidence of the incline of the road leading up from the river into the field was clearly visible when the writer was a youngster.

There was very little activity along the river during the eighteenth century, only the sound of Clark’s saws breaking the silence during the day. In 1710 a grist mill joined the sawmill, followed in 1715 by a fulling mill which employed a process of degreasing and softening homespun cloth made from sheep’s wool. During the next 70 years the site was occupied by four snuff mills, an annealing house, a wire mill, screw factory, blacksmith shop and another grist mill. Mill owners bore such names as Clark, Parker, and Elliot; the last name remains to identify one of the village’s principal streets. The backgrounds of all these pioneer mill owners are of great interest and may be found in many local histories of the area.

From Fishing Ground to Park Land

If we close our eyes and listen we might ‘see’ and ‘hear’ the sights and sounds so evident here almost a century ago. The voices of hundreds of people, the stirring marches of a military band, the toe tapping tunes from an orchestra calling dozens of couples onto the gleaming floor of a dance hall, the nostalgic sound of a merry-go-round and the laughter of children. Sounds lilted and drifted out into the vastness of space and timelessness. In 1893, near the banks of the river both on this field and the rise of land beyond was established a recreational area called ECHO BRIDGE PARK. This park preceded by about three years the more well-known Noumbega Park downstream. It was equipped by a public spirited citizen and a complete description is supplied by two news items appearing June 13 and 23, 1893:

“The citizens of Newton and surrounding towns now have a pleasure resort, the need of which has long been felt. The beautiful grove in the vicinity of Echo Bridge, which divides Upper Falls and Needham has been leased to a public spirited gentleman, and under the supervision of Mr. John R. Hall, the well known architect of Boston, hundreds of workmen have within the last two months transformed the grounds into a little fairy land. Echo Bridge was built by the city of Boston many years ago as a means of conveying the large water pipes from Lake Cochituate, and is considered one of the finest structures in masonry in the country. It is also of wide special fame on account of its grand echo, which attracts hundreds of people to the spot. The architect has built two large bridges over the Charles River. These lead to a broad staircase, extending up the cliff 30 feet, with broad landings, to the winding pathways, shaded by stately elms, oaks and pines, direct to the center of the park, situated on an oblong shaped hill.

A large dance pavilion has been erected on the Gothic style of architecture, 40 x 100 feet, open on all sides, with a high pitched roof. The pavilion is enclosed, with seats extending around. The floor is of maple. Adjoining the pavilion, and extending down the slope, long rows of seats have been erected, facing the music stand. At the foot of the slope and facing the pavilion Mr. Hall has erected a two-story octagon music stand, 20 feet in diameter. The band will be placed in the second story, which commands a view of the entire grounds. The lower story will be used for the refreshment stand, the shutters opening in a manner to form a roof around the building. The whole is finished with a high polished roof, with a flag staff at the top. Distributed over the grounds are some 300 seats, similar to those on Boston Common. Accommodations have been made to seat 2,500 people. The entrance to the park is from the Newton side. Located near the entrance is an old fashioned mansion of the colonial style, and the building will be used for the sale of refreshments, conducted on temperance principles. The grounds are well supplied with swings, merry-go-rounds, etc., with lavatories for both ladies and gentlemen.

These beautiful grounds were thrown open to the public last Sunday afternoon. In the evening they assumed an additional splendor by the illumination of the electric lights, casting their rays upon the whole of Echo Bridge, displaying the immense granite arches, the falls and the beautiful winding Charles River. The new bridges were lighted with red, blue and white in large glass globes. For picturesque scenery the spot cannot be surpassed. Fern-covered rocks, the falls, umbrageous groves, precipitous banks and bridges reflected in the deep, still waters, all form one of the most charming pictures that can be imagined. The attendance was very large on Sunday evening, an excellent concert was given by the Crescent Band of Waltham. The Echo Bridge Park, above described, is now open to the public every day of the week including Sunday. There is no quieter nor more beautiful spot in the entire city where women and children may resort during the afternoon, situated as it is in the midst of beautiful scenery, and shaded by pines and hemlocks.”

All this was made possible by the coming of the new electric street car rai1way to the village. It is recorded that on a pleasant Sunday afternoon as many as 5,000 people came here by that means to enjoy the beautiful surroundings. However, for some reason architect Hall’s charming creation was doomed to be short-lived. Two years later, in 1895, the Metropolitan Park Commission (predecessor to the Metropolitan District Commission) acquired the area. Charles Eliot, the man who helped organize the Trustees of Public Reservations and was the first landscape architect of the Metropolitan Park Commission, funded in 1895, repeatedly urged the Commission to acquire the Hemlock Gorge Reservation which he described as one of the most beautiful spots in the metropolitan area. After the acquisition Eliot further urged that Frederick Law Olmsted, founder of American landscape architecture (under whom Eliot had served as apprentice architect), be retained to design a detailed sight plan for the new reservation. News that this eminent individual was to redesign Hemlock Gorge in a manner that would eliminate Echo Bridge Park probably was received with mixed feelings by the local populace. Yet they may have felt honored to gain the attention of a man who designed, with his partners, 89 parks in 30 states! His works include Central Park in New York, the grounds of the United States Capitol in Washington, the site plan for Stanford University, Mount Royal Park in Montreal, the plan of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and an elaborate system of parks and parkways in Buffalo.

Mr. Olmsted’s achievements in the Boston area are equally outstanding. Most everyone is aware of all his accomplishments in the creation of the series of beautiful parks within the city of Boston that extended into a number of beauty spots out in the suburbs, popularly called Olmsted’s “Emerald Necklace.” We like to think Hemlock Gorge was the pendant of his Necklace as it is considered to be among his last achievements before an illness forced the conclusion to all his activities. The writer was fortunate enough to have seen some of Olmsted’s large drawings of the area in his office before the building became an historical museum. But one will always remember Echo Bridge Park. It probably represents the last use of private money in the major development in Hemlock Gorge.

Our Tour Continues:

Indian Field to the Upper Dam Overlook

At long last, we are now able to leave Indian Field (if we may call it that) and move across to its northwest corner and enter a lofty canopy of trees. As we move on to the main path we find there, we are confronted with a choice. Shall we remain on this wider path or take an inviting branch to our right? Our guide will probably suggest we accept the second path’s invitation. After a short but pleasant stroll along a tree covered lane that winds around the hill on which the old dance hall was once located, we emerge out into the open onto a rocky ledge that protrudes like the bow of a ship into the rushing current of the river, agitated by the turbulent discharge of a waterfall. Our guide will have to raise his (or her) voice to be heard over the passage of this noisy flood pushing its way downstream, but the history of this place makes the telling worthwhile.

Many a moccasin has trod this ground, one of the favorite fishing spots of the Indians. You may recall our earlier explanation of how the height of the dam proved to be a barrier to the salt water species of fish attempting to find a spawning ground further up the river. As they futilely leaped high in the air in their attempts it made them targets for the Indian spears. No doubt a friendly rivalry existed among the braves as each one tried to spear and net the most fish from this vantage point.

It may not be easy for us to imagine we ‘see’ the little sawmill on the opposite bank of the river and hear the ‘thump’ of its mill wheel competing with the sound of the saws they powered. A pile of logs would nearly fill the small area in which the mill was located, logs that were perhaps dragged here by local farmers over the hard ground or snows of winter. Clark sawed out their lumber, no doubt keeping a certain amount for himself as his payment. Other logs might have reached here by being floated downstream on the high water of Spring.

As we have learned, during the next century other mills joined this lone sawmill. Joining Clark were other mill owners with names such as Parker and Elliot. Elliot’s daughter, Sarah (Sally) married Thomas Handasyd Perkins, well-known Boston merchant prince. Perkins and his brother James in 1823 had bought most of Elliot’s holdings and constructed the brick buildings we see on the opposite shore.

How long the Native Americans remained on the western shore of the river we do not know. The sale of their land and the effects of the plague that swept through many of the New England tribes in the early seventeenth century thinned their numbers, with some tribes affected more than others. By this time the British flag that had flown over this spot for 150 years had been replaced by the forerunner of the Stars and Stripes. It was now part of a new nation and the demand for its products taxed the limits of the waterpower that turned the belts and pulleys of its mills.

We may want to contemplate this history while we are standing here above the upper dam of the gorge but a glance downstream will, (for the first time for some) reveal our first view of the magnificent seven-arched Echo Bridge as it soars high above the gorge to cross the river below. Though we are eager to see the view from its top we will save this treat until later when we give you the dimensions and details regarding this remarkable structure.

The Upper Dam Overlook to the Gorge Overlook

So, perhaps reluctantly, we return to the main path and turning to our right ascend to where the right-of-way of the aqueduct pipe line crosses our path on its way to the bridge that will carry it across the river. Resisting a temptation to turn in that direction we continue on the main path that leads us under a dense arbor of trees that crowns the high ridge of the gorge, paralleling the river. We will soon come upon a trail leading off to our right that leads down the steep side of the gorge to the water’s edge. Here we will cross a narrow stream on a footbridge to a tree-covered wedge-shaped point of land lying between the small stream we have just crossed and the main channel of the river a few feet away.

The Second Overlook to Artist’s Point

From this point, face directly upstream to enjoy a fine view of the northern side of Echo Bridge and within its huge arch, a delightful almost miniature view of the mills and the river as it leaves the upper dam. For years this picturesque view brought artists from all over the world to capture this scene on canvas. It is said it was only surpassed by ‘Motif No. 1,’ the ancient red building and wharf located in Rockport (Massachusetts) Harbor.

At this point we have a choice as to how to proceed further along the gorge, with the lower dam our destination. We can return to the narrow stream we just crossed and follow a trail along it through an area called Barker’s Glen, proceeding past a control gate once used to regulate the flow of the river by the mill owners. Excess high water in the spring was siphoned off to a holding pond at the end of the small stream called ‘New Pond’ and, in reverse, water was returned to the river at low water time in the summer.

At the end of the small stream there was once a ‘Z’ shaped bridge which our organization ‘Friends of Hemlock Gorge’ are hoping to replace in some form in the near future. It would face an outcropping of ledge that contains the rocky cave known as ‘Devil’s Den’, where it is said the Native Americans stored their dried fish for the winter. We are now only a few feet west of the lower dam, the sound of which is now clearly heard.

For the record, we will return to the area we called ‘artists point’ and in our mind’s eye describe the alternate path to the lower dam. It will follow the bank of the main channel of the river, an attractive ‘open’ route. Almost immediately you will note where the river once divided into two branches called the East and the West. While the West Branch now represents the main channel, the East was once strong enough to operate a number of mills located on both sides of the Worcester Turnpike. No longer needed for that purpose it has been reduced in width and also controlled by a ‘gate’ for a similar purpose as the stream through Barker’s Glen.

We Reach the Lower Dam

Artist’s Point to the Lower Dam

You may recall this observation was made from the Barker’s Glen path so we would continue on to meet up with that path at the lower dam, now called the Horseshoe Dam because of its shape. It occupies most of the width of the West Branch. It is not the original dam. The dam you see was constructed in 1905-6 to control the 10 foot drop in the river at this point. In most accurate detail we include here a news item regarding this dam taken from the TOWN CRIER of October 7, 1905. Note that it also includes information regarding the old dam and the early mills it once powered:

“The most interesting engineering operation going on at present in this vicinity is the building of a new bridge and dam at Boylston Street. The foundations of the dam have been laid and the downstream half of the main arch is well advanced. The arches are of concrete, reinforced with steel rods and the exposed faces are of granite. The dam is to be of granite and is to be circular in plan except at the Newton shore where the floodgates are to be located. The dam is located south of the new bridge while the old dam was north of the old bridge, so the water falling over the dam will easily be seen from the bridge. The first bridge was built here in 1808 at the time the Worcester Turnpike was first started. The first dam was built in 1783 to furnish power for a saw mill. This dam and its successors furnished power at different times for a saw mill, rolling mill, cut nail factory, cotton factory, grist mill, planing mill and paper mill. The new work is being done jointly by the City of Newton, the town of Wellesley, the counties of Norfolk and Middlesex and the Metropolitan Park Commission and when completed will be a great improvement to the already beautiful Hemlock Gorge.”

Most of the mills named in editor Temperley’s article were originally located on both sides of the old Worcester Turnpike, mostly on the Newton side on an island located between the branches of the river, known as Turtle Island. Rufus Ellis, one of the early mill owners in the area had some difficulty in establishing a location for his new mill as indicated by the following account found in Clarke’s HISTORY OF NEEDHAM:

“On June 21, 1803 Turtle Island in the Charles and one-quarter of a mile below the Upper Falls so-called in said River being the same Island, upon which the Newton Iron Works Company have erected their Manufactory, was taken from Needham and annexed to Newton – on petition of Rufus Ellis, the agent for the Newton Iron Works.”

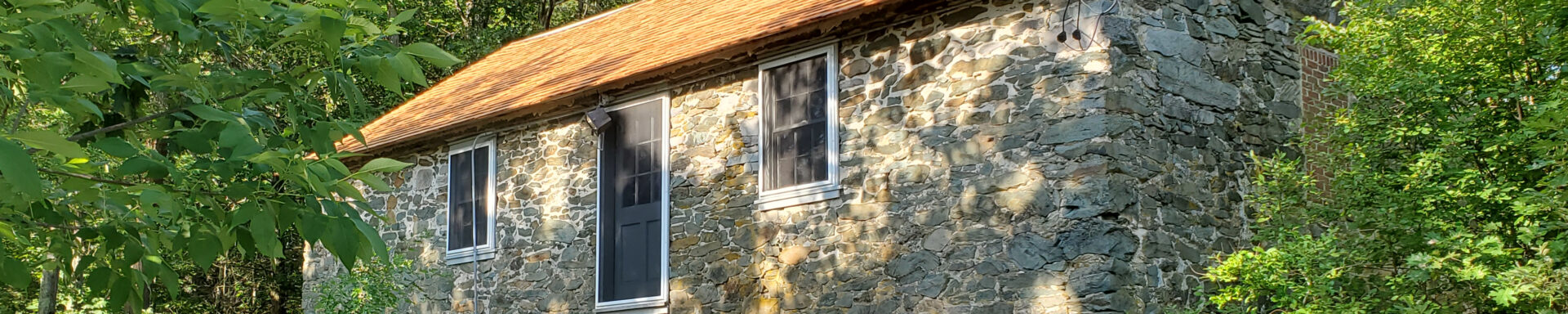

One mill did get built across the river on the Needham side (now Wellesley). It was built in 1813, destroyed by fire in 1850; rebuilt in 1853 and again destroyed by fire in 1873 and never rebuilt. The only building remaining of this industrial complex is believed to be located on its original site on the south side of the old turnpike opposite the building described above. Its purpose is something of a mystery. It is believed to have been built at the same time the 1853 building was being constructed across the turnpike. It does not appear to have been used too often commercially since its companion building was destroyed by fire in 1873. It was used as a meeting place for the Quinobequin Club (an all male organization of Newton Upper Falls) and later became their ‘clubhouse’ when they organized one of the first golf clubs in Newton. Its course was laid out across the turnpike, between the river and Chestnut Street. Later, when they had moved their meeting place to Nahaton Hall in the village, the Newton City Directory of 1885 shows that James Easterbrook, a varnish maker, occupied the building until his death in 1890. The building was acquired by the Metropolitan Park District Commission in 1895. It later was used to house Federal Government equipment for gauging the flow of water over the Horseshoe Dam.

Our Tour Turns For ‘Home’ Over a Different Route

We will now continue our tour along Boylston Street toward Ellis Street. Perhaps we should make some comment about this old highway. It is among the first major highways built in Newton and was very important for facilitating the shipment of their goods to and from domestic and foreign markets. Soon after it was built in 1808, the War of 1812 resulted in a blockade of Boston Harbor by the British Navy and most of the freight traffic was confined to shipments to domestic markets only. Huge Conestoga-type wagons, humorously called ‘Madison’s Ships'(after the president in office at the time) and hauled by 10 horse teams, were used to move freight up and down the seacoast. They drew large crowds to the highway to watch their passage. In 1829, Abbott & Downing’s new ‘Concord Coach’ (an improved version of an English coach) passed through the village in a record run from Boston to New York in less than twenty-four hours, “causing the church bells to be rung and at night bonfires to burn on all the hills along its route”.

In 1902, about a century after it was built, the turnpike experienced its first alteration when the Boston & Worcester Street Railway Company secured a franchise from Newton to operate a two-track trolley service over the highway. The road was widened to a width of 90 feet, the two rails laid side by side in the center with a highway on each side. As part of the agreement street lights were added along the highway. With the recent construction of Echo Bridge and the completion of the park facilities by the MDC, the street car line provided easy access to this attractive area. Also, only ten years before (1892) the Newton & Boston Street Railway had arrived in Newton Upper Falls. The narrow entrance from Chestnut Street onto Echo Bridge must have been crowded as it is said about 5000 passengers were carried here by street car on pleasant Sundays. On June 10, 1932 the last Boston & Worcester street car was operated from Park Square to Framingham and the service was replaced by buses over the entire system. This was made necessary by the construction of the state highway (Route 9).

Originally Ellis Street made a sweeping curve to the right before it reached the turnpike. Its old course can be noted today by the stone wall that still remains to mark its eastern side. When it was rebuilt in its present location, the land on the west side of the highway beginning with the Baptist Church property was acquired by the MDC. The land on the east side remained with the original owners except that required by the construction of Echo Bridge. A house once located on the left side, at the end of the old stone wall previously mentioned, was removed leaving for a long period of time, an empty and unsightly ‘cellar hole.’ One the house once located here was Daniel Keefe, born in Castle Irons, County Cork, Ireland, coming to this country in 1846 at the age of 22. He died in 1904 and was survived by his widow, two daughters and a son. It is said Mr. Keefe maintained an active interest in local affairs.

The ‘cellar hole’ was has been replaced by a beautiful lawn and flower garden created and tended by a nearby homeowner, Mr. Paul E. Melanson. More recently, in 1996, the Friends of Hemlock Gorge beautified and dedicated a long awaited parking lot at the corner of Ellis Street and the Route 9 off ramp that was once Boylston Street. This small but much needed lot was been built by the city of Newton as a direct result of advocacy by the Friends who contributed $400 towards the cost of planting flowers and a tree around the lot. The Upper Falls Community Development Corporation matched this amount. The landscaping plan was designed by Kenn Eisenbraun of the Newton Planning Department. Kevin R. Hollenbeck of the MDC purchased the flowers, tree, and other supplies to implement the plan. The Friends joined the MDC staff in the actual planting in the spring of 1996. It is a bright spot on our tour.

At the point where the original curve in the old Ellis Street began another broke off and made a reverse curve to the left, leading down to the turnpike. It served the nail factory on this side of the turnpike as well as the mills across the turnpike. Located in the area between the two curving ends of Ellis Street was a large boarding house for workers in the mills and their families. It was originally owned by Frank Barden, a mill owner. It was sold when the mill property was acquired by the MDC and believed to have been moved further up the turnpike into Upper Falls and is possibly the building now located at 1304 Boylston Street.

As previously indicated, the property of the first two residents located on the west side of Ellis Street was acquired by the MDC; the first house previously owned by J. Sheridan (probably since moved elsewhere in Upper Falls) and the next (located in the shadow of the new bridge) belonged to H.W. Fanning, a member of a well known family of business men in the village. The house, however, vas retained by the MDC to be used as a home for the caretaker of the bridge and park property. (When this use was discontinued by the MDC, the building remained vacant and was destroyed by fire set by vandals). There vas another house, located close to the site of the bridge. It was owned, (but probably not occupied) by a ‘C. Ellis’ (Charles Ellis, a mill owner who lived on Boylston Street Hill in the Ellis mansion). It was sold to an unknown buyer who moved it to what is now 32 Williams Street in the southern section of the village.

We ‘Talk’ To a Bridge and Listen to its Reply

Up Ellis Street to the Echo Platform

We pause now on our tour at the point on Ellis Street where it passes through a 38 foot wide arch under Echo Bridge. But before we take the stairs in the embankment to our left that would take us to the top of the bridge we will turn right to visit one of its most attractive features, the echo beneath its massive main arch that crosses the Charles River in one sweeping loop. We follow the path that takes us down the east bank of the river, down past the large stone piers supporting the huge weight of concrete and stone, and after descending a set of stairs we arrive at a platform, extending under the vault of the 133 foot arch, an awe inspiring sight. [Editorial note: The platform was restored in 2004.]

Our first shout is embarrassing to us – it’s a timid one – something we do not ordinarily do in public. But it will be amusing when after your faint “Hello” you receive in return a friendly greeting by its echo. This warrants another try, a little louder this time. “HELLO!” And by golly it came back twice! Then you remember, they said if you yell loud enough you can hear your echo return your greeting 15 times. Well, here goes,“HELLO!”Stamp your feet and you can command a brigade in full parade. Get two or three people to play an instrument with you and you are the Boston Pops! But say nothing and listen carefully and it is said you will hear the voices of our long departed Indian friends, wishing you well.

From the Echo Platform up “to the top”

Reluctantly we leave to make our long upward climb to the other side of the arch. When we descend the stairs onto the walkway across the bridge we find the ‘view from the top’ certainly is a delightful one, among the loveliest you will ever witness. Of course, there are the practical ones who wi11 want to know how many tons of cement it took to build ‘this thing.’ So whether or not you take an esthetic view or a practical one we will run through all the statistics regarding its construction, etc. Regardless of what view we take we will all have a deep respect for this beautiful structure known as Echo Bridge and for those who brought it into being. Our source of information regarding all the features of the bridge comes from a number of places, most of which have been brought together in our previously mentioned book.

Construction of the bridge by the Boston Water Board was started in the spring of 1876 and completed in November 1877 at the cost of $200,000. During its construction no accident occurred to any workman or to the machinery! The bridge is 500 feet in length and consists of seven arches, five of 37 feet span and one (over Ellis Street) of 38 feet. The seventh and largest arch, which spans the river is said to be the second in size on this continent and one of the largest stone arches in the world. At the time of construction its size was exceeded only by the Cabin John Bridge in Washington, D.C. It is segmental in form, 130 foot in span, with a radius of 69 feet The crown is 51 feet above the usual surface of the river. The keystone is five feet in depth with the archstones increasing to six feet at the base forming a very heavy arch, and the pressure upon the foundation is about 2,900 tons, or about 16′, tons to the square foot. The foundations of the bridge are in solid rock. The timber framework upon which the arch was built rested upon five points of support in the bed of the river and demanded about 110,000 feet of spruce, oak, and hard pine timber in its construction. The settling of this framework which was caused by the weight of the archstones during construction was only about two inches. To one standing beneath it the arch has a very slender and beautiful appearance, tapering from 22 feet at the base to 18 feet in width at the crown.

As noted above, there is a remarkable echo within the arch with the human voice being rapidly repeated upwards of 15 times and a pistol shot 25 times. The inside section of the conduit carried within the bridge is equal to a circle eight and a half feet in diameter, its width is nine feet and height seven feet, eight inches. The inclination on the conduit is one foot per mile and its capacity, when filled to high water mark, is 80,000,000 gallons in 24 hours.

Today the system is not in use, serving only as a standby reserve in case of a breakdown in the water supply presently being received from the Quabbin Reservoir located in the center of the state. One of the largest reservoirs in the nation, Quabbin is expected to supply our needs for many years to come. However for almost 75 years, from 1877 to the early 1950’s, Echo Bridge carried its precious cargo of the ‘elixir of life’ to thirsty millions.

Fortunately, it has been preserved and still stands as an outstanding and beautiful example of nineteenth century engineering skill. On April 9, 1980 it was accepted by the National Park Service into the NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES. We are pleased to announce at this writing that the state has restored most of the decaying and damaged bridgework and the Metropolitan District Commission is beginning to bring back some of the beauty for which Hemlock Gorge is noted.

Our local organization, made up of citizens of Newton, Needham and Wellesley, and called the FRIENDS OF HEMLOCK GORGE has been organized and is working with the MDC to help accomplish the task. New members would be welcome. Consult your tour guide for more information.

Copyright Kenneth W. Newcomb, 1994, 1996, 1997, 1998

First Online Edition, December 12, 1996.