Reprinted with the permission of the author.

By Elisabeth J. Beardsley

STATE HOUSE NEWS SERVICE, www.statehousenews.com

[email protected]

STATE HOUSE, BOSTON, SEPT. 12, 2000

The Bay State’s official bug could soon wing to the rescue of one of the state’s favorite native trees.

Under a $60,000 pilot program included in this year’s budget, an army of Japanese ladybugs 10,000 strong will be brought to bear on the woolly adelgid, a nasty little insect that’s killing hemlock trees in this state and others along the East Coast.

The sap-sucking Asian aphids were introduced into North America in the 1920s, and have slowly been spreading northward. The woollies have ravaged Connecticut forests for years, and turned up in Massachusetts after being blown across Long Island Sound on the winds of a hurricane five years ago.

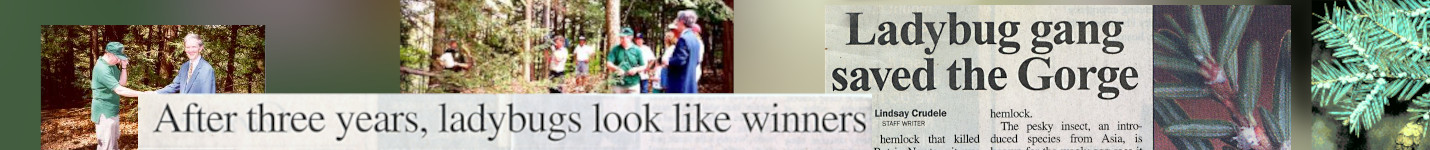

The pilot project will begin in Hemlock Gorge in Newton Upper Falls, an area particularly beset. Sen. Cynthia Creem (D-Newton) helped secure the money for the ladybugs, which are natural predators of the aphids, after taking Senate President Thomas Birmingham to the gorge to see the damage.

“You can see that the trees are dying, that the leaves don’t look good. You can see where they’ve changed color,” Creem said, adding that the 23-acre reservation is “gorgeous” and “means a lot to a group of people.”

In addition to the threat to the forest, Creem said local officials are being whacked with the cost of removing dead trees. Brookline spent $10,000 last year removing dead hemlocks from the gorge, she said.

Newton Alderman-at-Large Brian Yates, president and founder of Friends of Hemlock Gorge, said pesticides can be sprayed or injected into trees’ root balls, but it’s a temporary solution that can’t be used near water or on very large trees. Chemicals can be effective for a small number of trees, such as in a yard, but the risk of re-infection makes pesticides impractical for forests, Yates said.

The Friends of Hemlock Gorge hit upon the ladybug idea after a Connecticut researcher traveled to the adelgid’s native Japan in 1992 to find out why the hemlocks there were healthy, Yates said. He discovered that a poppy-seed-sized black ladybug, previously unknown, was keeping the adelgid population under control by eating the aphids’ egg sacs, which look like strings of fluffy little white balls.

The Japanese hemlocks “never got to such a stage that they would be vulnerable to dying because there were natural predators there,” Yates said. “In Japan, they’re in perpetual balance. We’re trying to establish the balance.”

After two years of research, the US Department of Agriculture issued a permit for the introduction of the ladybugs. Since 1995, 18,000 of them have been released into six hemlock forests in Connecticut and one in Virginia, reducing the adelgid populations by between 47 and 100 percent.

Sen. Stephen Brewer (D-Barre), whose district is also suffering an aphid infestation, has called a hearing on the menace this Thursday before his Special Commission on Forest Management Practices. With the virtual extinction of the American elm in mind, Brewer said, environmental managers must act now to stop the bugs’ northward march. They have already reached the Vermont and New Hampshire borders.

“They don’t pay any attention to political boundaries. Nature has its own agenda,” Brewer said. “They go into other areas and will upset the economy and strike an aesthetic blow to our environment.”

Hemlock fans are anxious to get the ladybug breeding project underway, hoping to release them into Hemlock Gorge next spring, Yates said. But the Metropolitan District Commission, which oversees project funding, has not yet chosen a breeder, he said.

MDC spokesman Chuck Borstel said Commissioner David Balfour and agency officials are discussing project priorities. The ladybug pilot is in limbo until the agency decides whether lawmakers appropriated enough money for it, he said. “Sometimes legislative estimates are not always accurate,” Borstel said. If the project gets a green light, he said the MDC would likely hand the money over to the Department of Environmental Management to figure out the details.

Not everyone is thrilled about the prospect of turning Massachusetts into ladybug-land. The Massachusetts Audubon Society is wary of the untrammeled use of “biological control agents” insects released to kill other, peskier insects. It’s suspected that such attack bugs had a hand in the extirpation of the Regal Fritillary butterfly from Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard.

Christopher Leahy, director of Mass. Audubon’s Center for Biological Conservation, said environmentalists are worried about the fact that Eastern Hemlocks are “next on the storm track” for the woolly adelgids, but they’re also concerned that the ladybugs might attack “good aphids,” as well.

“The worry is always that the foreign control agent may be worse than the species it was placed there to control in the first place,” Leahy said. “It’s a fairly new science, this biological control thing. The intricacies of biological interactions are such that we can’t possibly get our arms around them and know them well enough to predict accurately what’s going to happen.”

But Yates said the habits of the Japanese ladybugs are well known, and they only prey on woolly adelgids and one other type of insect, the latter of which makes the ladybugs infertile. “This is a very species-specific predator,” Yates said.

Brewer said he’s anxious to hear the pros and cons of biological agents, but he noted that natural predators are probably better than spraying noxious pesticides, which can seep into the water table and cause further harm to plants, animals and humans.

And Creem added, “What’s the other answer? Let all the hemlocks die?”