Colonial Schools in Cambridge and Newton

Francis Jackson in his HISTORY OF NEWTON records the following, taken from early town meeting records:

“1698 March 7 – ‘The Town voted to build a school house as soon as they can!’”

This vote, cast by a handful of home owners and land owners in their drafty and barn-like church on the old Dedham Road, is the first record of Newton’s desire for its own school. S.F. Smith in his HISTORY OF NEWTON from similar records of the same year (possibly at the same time as above) tells of another need that required official action: “Voted, that a vane be provided to set upon the turret of the meeting house.”

Whether the old meeting house, built in 1660, got its vane is not known but Jackson reveals that “the erection of the school house was near a half century behind that of the meeting house.” To learn why, let us begin at the beginning.

Newton, as was the case with most New England villages, shared in the inheritance of a sound educational system from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, creating the intellectual foundation upon which a new nation was built. The colony, having arrived in Boston to establish a permanent home, sought educational freedom as well as freedom of religion. Their leader, John Winthrop, who had received his education in Trinity College, had surrounded himself with university trained men from Oxford and Cambridge. With one university trained man to every 40 or 50 families and a large but indeterminate number of men who had a sound classical education in the English grammar school, education was of great importance to the newcomers. Evidence of their zeal may be found in the fact that Boston Latin School was founded in 1635, five years after their arrival, and Harvard College was established the following year in Cambridge. In 1638 the first printing press in the American colonies began operating. By the year 1700 most of the people of New England could read and write.

Samuel Eliot Morison, in his book, THE INTELLECTUAL LIFE OF COLONIAL NEW ENGLAND – ( New York University Press – l 956 ), states:

“A careful combing of lists of immigrants reveals that at least one hundred and thirty university alumni came to New England before 1646. This does not seem a very impressive total; but the entire population of New England in 1645 was not greater that 25,000…which means that there was on the average one university-trained man to every forty or fifty families. In addition there was a large…number of men who had a sound classical education…and therefore saw eye-to-eye with the university men on intellectual matters…”

These men, rising to positions of leadership, created among their fellows a high desire for a sound educational system in the colony. Laws were enacted very early to create such a system. The first, enacted in 1642 and amended by an Act of 1647, required that a Massachusetts town of 50 families must establish an elementary school where children could learn to read and write; and that a town of a hundred families or more:

“…shall set upon a Grammar-School…to instruct youth so far as they may be fitted for the Universitie.” The English grammar schools accepted boys at the age of seven or eight. Seven years were considered sufficient to prepare them for college whose entrance requirements were about the same as those of Oxford or Cambridge. Since American grammar schools were set up along the same lines, including an emphasis on the study of Latin grammar, most students opted for only an elementary school education. Later, if they desired to go on to college, they turned to private schools to complete their studies. However, not many were financially able to achieve such a goal. Records show “the total number of college students in the seventeenth century was less than six hundred, of whom 465 graduated.”

With such strong religious leadership, one would naturally assume that the Massachusetts Bay Colony schools would be strictly church schools. However, as Morison says, “They were, in every contemporary sense of the word public schools.” It is true that in 1701 (the year of Newton’s first school) a provincial law required grammar schools be approved by the ministers of the town, and the same law ruled out town ministers from themselves qualifying as grammar schoolmasters. Still, the intent of the licensing provision was “to ensure proper scholarly qualifications….” Aside from the practice (which many of us still remember) of school opening and, in some institutions, closing with prayer, they established the present American system of free public education for all (emphasis added.).

When Newton took that first vote in March 1698 to build a schoolhouse “as soon as they can” it would have seemed that a schoolhouse would soon be a reality. But we find that a year later, in May, 1699 they were still voting – “to bulld a schoolhouse,16 x 10 before the last of September.” On January 1, 1700 they decided on a teacher, John Staples, and finally, after Abraham Jackson gave the town an acre of land near the old meeting house for the site of the school house, they completed the erection of the building on March 14, 1701. However, for some reason it was voted in 1742 …“to remove the Centre school-house, to the Dedham Road, and to place it ‘between the lane that comes from Edward Prentice’s and Mill Lane, where the committee shall order.”

Evidently inspired by Mr. Jackson’s generosity, that same year Jonathan Hyde, Sr. gave the town “half an acre of land near Oak Hill, abutting ten rods of the Dedham Road (Dedham Street) and eight rods northwest of his own land, for the use and benefit of the school at the south part of the town.” We perhaps should consider the schools well located. One near the meeting house was certainly an advantage, and our historian tells us that at that time Oak Hill was “the most important and thriving portion of the town.”

It would appear that the education of children did not seem to be of great importance to the early residents of Newton, for one of the reasons had a familiar ring to it – the inhabitants were not anxious to increase their taxes for any purpose. Also, with but a limited population spread over a wide area it was a difficult task financially for the town to come to grips with the proposition of providing more schools. Actually, at one time a petition was circulated which proposed that there be but one schoolhouse in the town. When money was finally appropriated it was only to support schools conducted in private homes.

It might be well to pause here and remind our readers that Newton had no opportunity to establish educational facilities until after its separation from Cambridge in 1688, and its distance from the parent village precluded the children from taking advantage of an excellent grammar school located there. Aside from the handicap of distance it would have been a great benefit if the residents had exercised their right to its advantages, especially if the student’s ambition included graduation from college. The school was founded in 1643, was located near Harvard College and attained a fine reputation as a seat of learning. The school appears to have been started by a university graduate who operated it for some time without assistance from the town. Morison tells us that the school:

“…unlike some of the grammar schools of Oxford and Old Cambridge, has no organic connection with the College but on account of its situation and the fame of Elijah Corbet (B.A. Oxford and M.A., Cambridge), the master of fifty-five years, it attracted boarders from other parts of New England; and from 1672 to the end of the century it sent more boys to the college than any other school.”

The town of Cambridge was taxed for this school, in which their sons were to be fitted for college, and the inhabitants of Cambridge Village bore their share.

In the proposal made by Cambridge in 1672 to quiet the inhabitants of the Village, and which the General Court sanctioned in 1673, the Village was required to continue to aid in supporting the grammar school and had an equal right to its advantages. But it was many miles away from Cambridge Village, and aside from the fact that the Reverend John Eliot, the first pastor at Cambridge Village, received the rudiments of his classical education here, it is very likely that few of the sons of the settlers attended the school, and were there fitted for college.

By the time Newton became free to establish rules for the education of its youth, it found that the school systems of its neighboring villages were much further advanced. Most seacoast towns and many inland villages had established their schools in the seventeenth century. For example, Charlestown’s first school was established in 1636, only a year later than the Boston Latin School which was the nation’s first. Salem, Ipswich and Newbury all had schools well in place before 1640 while Dorchester’s first school opened its doors in 1639 and Roxbury’s in 1646. Neighboring Watertown had its elementary school in operation in 165l. In contrast, Plymouth Colony had not established a school, albeit a grammar school, until 1673.

In 1642 Massachusetts first compulsory school law (the first in the colonies) required that every child be taught to read. However, the first provisions for primary schools were confined chiefly to boys and it was not until the year 1789 that the law was modified so as to allow girls to attend. Before the end of the eighteenth century, in nearly every town in the Commonwealth arrangements were made for the education of girls, especially in the summer. As late as the year 1820, however, the public school in Boston admitted girls only from April to October. Female teachers were employed by the towns earlier than this, as it is noted that in 1766 Newton voted sixteen pounds to employ a schoolmistress, and our historian goes on to say that this was the first “woman’s school”. But were they using the Boston system? Records of our schools in Upper Falls in the 1830s show that women teachers were employed for the summer sessions and males during the winter.

Following the erection of the two schools already mentioned in 170l, another called the “west school” was added in 1726. It was a new building located near the “house of Samuel Miller” in the West parish (West Newton). Previously Miller had supplied a room in his house at no cost to the town. His gift of land for a new school is revealed in this record:

“Samuel Miller was the son of Joseph Miller, who lived on the Stimpson Place, West Parish. Besides the offer of a room in his house for a school, he gave the town in 1726 four rods of land near his house for a schoolhouse.”

The Miller homestead was located on the road to Lower Falls near its junction with the present Woodland. Street or Old Worcester Road. It was not yet in “West Parish” as that village (later West Newton) did not build the second church in town until 1764,

During the decade 1750-1760 there were a great many discussions and committees formed in town meetings relative to school matters, including one “to provide a Grammar School master to keep the Grammar school the ensuing year.” However, it is felt that the term “Grammar School” did not mean a school where “Latin and Greek languages were taught; and where young men were fitted for college” as required by the law of the Great and General Court. No record exists showing that this type of school was established at that time. Possibly the use of this term in the committee assignment might have appeased a Legislature not anxious to become involved in the law’s enforcement.

In 1763 the Southwest District School was established, described as a brick building 14 X 16 feet square. It was built west of the present railroad (MBTA) between Boylston Street and the old Sherburne/Upper Falls road; “near the late Nancy Thornton’s residence, once the Mitchell Tavern.” Smith’s History comments that “the house was covered with a hip roof, coming together at a point in the centre; a fireplace about six feet wide and four feet deep with a large chimney, in which they burned wood four feet long, occupying one side of the room.” it continues, “The house became very dilapidated, and the roof so leaky in its later years, that it was not uncommon for the teacher to huddle the scholars under an umbrella or two, to prevent their getting wet during the summer showers.”

Another source says that this old building was not replaced until 1811 by another building further west, on the north side of Elliot Street near the present MBTA bridge. However, while this latter building was built at a later date, the writer was surprised, to find, by happenstance, a deed in Cambridge courthouse which indicates that the 1763 southwest schoolhouse was replaced in 1794 by a new brick building paid for principally by local residents and mill owners of Newton Upper Falls whose names are included in the deed. The document further indicates they intended to sell the building to the town for l00 pounds. This is verified when the town, in accordance with a policy established in 1794, sought to gain control of their school property. Historian Smith indicates the result:

“The school-houses had hitherto been the property of the several districts, having been built wholly or partly by funds provided by the people who expected to enjoy benefits from them. But in 1794, the town voted to purchase as many of them, with the land appurtenant, as could be obtained on reasonable terms. The proprietors of the east school-house estimated their house at 40 pounds; south school-house 90 pounds; southwest l00 pounds; north 20 pounds; the proprietors of the west school-house referred the estimate of theirs to the committee appointed by the town.”

Note that the valuation placed on the southwest school was l00 pounds, the exact amount of the sale of the school by the Upper Falls residents of the town.

You will also note in the school valuation account above that the town boasted of having five school districts. In 1766 the town had voted to raise their school districts to five and the newest school added was the “North”, built on land “formerly occupied by Abraham Jackson’s blacksmith shop”, believed to be on the old Natick Road. (Washington Street) opposite present Jackson Street. In 1790 one more school district would be added, that of Newton Lower Falls, Newton’s first independent district. The town at this time was attempting to tighten its control of what appears to have been a rather loose school system. There had been one school committeeman to watch over the interests of each school but, unfortunately, they were changed quite often. Smith tells us that “almost the entire Board at some periods, was, annually, a new one.” However, the day of the industrial revolution was dawning and the mill towns along the river, particularly Upper and Lower Falls, were soon large enough to handle most of their own school affairs. The Lower Falls school district established in 1790 and that of Upper Falls in 1824 would be the only two village schools in place in Newton prior to the introduction of the townwide system of grade schools in 1855.

Before we bid farewell to the eighteenth century we shall recap for the records the number of schools built in that period and their locations: two schools built in 1701, one at East Parish (Newton Centre) and the other at Oak Hill; one built on “Miller’s land” in West Parish (West Newton); two in Upper Falls-Oak Hill in 1763 and 1794; one in 1766 at Angier’s Corner (Newton Corner); and one erected in 1790 at Lower Falls.

The Nineteenth Century

By the beginning of the new century Newton had already commenced to assume its unique character of representation by a number of more or less independent villages. A total of six provided the foundation upon which the city was built. They were East Parish (Newton Centre), Upper Falls, Lower Falls, Angier’s Corner (Newton Corner), North Village, (Nonantum), and West Parish (West Newton).

The dawn of the new century saw no changes nor brought any further enlightenment to Newton residents that indicated any advancement to more than an elementary education for their youth. It was the beginning of the town’s first complete century and school business proceeded as usual. On May 16, 1805 a town meeting appointed a committee “to prepare a general plan of schoolhouses and schooling.” This committee reported on May l2, 1806:

“…that it is their opinion that the town erect, as soon as convenient, six schoolhouses, exclusive of that of Lower Falls, which is to remain at present where it is now; the other five to be sold, and that a new one be erected… in the west district, near the house of Amasa Park…”

In 1808 school districts were known as “School Wards” and there were eight of these. That same year, $800 was “proportioned” out to the wards, the largest amount to any school $126 – the least $105.

At this point the result of the industrial revolution was making itself felt in the mill villages, particularly in Upper Falls. The rapid increase in the population of mill workers, many with large families, brought a demand for schools unprecedented in the town before or since! More schools, both district and village, would be built within its village limits than at any time in any other village in Newton. Personal journals and records make it possible these many years later for us to obtain a complete record of the scholastic development of the village, the only record of any school activity in Newton during its early years. Complete descriptions of the quaint one-room schoolhouses of the early 1800s are only alluded to in our history books, whereas these journals give us accurate accounts of these nostalgic but exciting early school days of our nation.

The 1794 district school on the easterly outskirts of Upper Falls soon found itself standing in a sparsely settled part of the village as an expanding number of industries in the village proper drew a growing population of mill workers closer to their jobs. This meant abandonment of the 1794 school and in 1811 the erection of a new school on Elliot Street, near its junction with Woodward Street and the Worcester Turnpike. It soon became known as the Cook Schoolhouse, honoring Deacon Asa Cook who lived nearby. A news article appearing in the TOWN CRIER in 1905 indicates that this 1811 school was about 22 x 28 feet in size (see more complete description following) and was located on the (north) westerly side of Elliot Street, and that “the school house stood beside a very tall, forked pine tree which had been a landmark for generations until it was felled to make room for the railroad bridge when the Circuit Railroad was built.” (More about this later).

The One Room Schoolhouse

While S.F. Smith gives us a general description of a typical schoolhouse of the period, we are fortunate to have an actual description of this 1811 school by George Pettee who attended there in the 1830s:

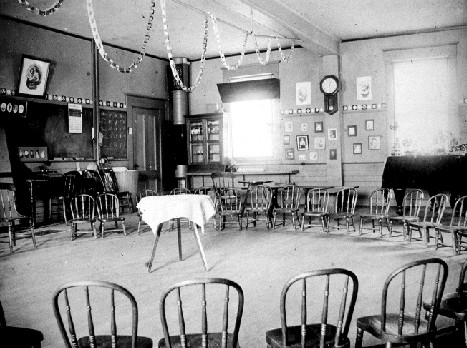

“Please have in your mind’s eye, a one story building from thirty to thirty-five feet square, with three large loosely fitted, rattling windows on each side, and two at each end, guarded with blank shutters, standing upon an open, bleak location, and you have the outside of the rookery that seventy of us children were sometime packed into, while attending school. Now remove the pad-lock, open the door and step into the entry, which is about eight feet that extends across the building, and is well stored with firewood. Pass to the inner door, and take a look into the schoolroom. The centre floor is twelve feet wide with master’s high desk at the opposite end. You will notice a box containing a terrestrial globe, the only mechanical device we ever had in school, and a rough specimen of a plain cast-iron stove near the middle of the room, designed for burning wood, thirty inches long, with a staggering stove pipe, having several uncertain angles that tend to guide it through the ceiling into a suspended chimney.

On each side are fifteen desks, arranged in three rows, each desk to accommodate two pupils, with the floors for the desks raised from twelve to sixteen inches higher at the wall of the room, than at the centre. The dado of the walls form the backs for the first class seats, and the seat is a plain board, say ten inches wide, placed at right angles with the walls and at a convenient height from the floor. This seat extends the whole length of the room, and directly in front are five desks, leaving four open spaces; the end desks are fastened to the wall, so the inside occupants cannot leave their seats without disturbing their deskmates. Other boards are secured to these desks, as seats for the second row, and this row makes the back for the third row of seats, and a cricket, without desks, is fastened to the lower row for the juvenile scholars – girls on one side, boys on the other and all facing the centre floor of the room.

We had two terms each year, the summer term was taught by a mistress to the young children and the winter term by a master to all ages. The terms varied from thirteen to seventeen weeks duration. We were in school six hours each day, but had one day off from study every fortnight.”

A description meticulous enough to be a model maker’s delight!

We shall return later with more of George Pettee’s school day activities in the little one-room 1811 schoolhouse, but let us first discuss the rapidly developing events in the village proper. For the same reason the 1794 school was abandoned and the Elliot Street site selected for the 1811 school, it was necessary to consider another school much nearer the village. A rapid increase in population resulting from the industrial revolution which the nation was experiencing resulted in a boom in the village’s economy and size. For at least the first half of the nineteenth century, Upper Falls was Newton’s largest village. Much of the industrial activity took place at the lower dam on the river where it passed beneath the Worcester Turnpike. This activity produced more pupils than the 1811 Elliot Street school could handle and a new school was built in 1818 on the southwestern corner of Chestnut and Boylston Streets in order to accommodate them. George Pettee would later record this:

“The children from the vicinity attended school in the (old) southwest district, but; as the business increased and the village became more populous, it was necessary to divide the district and build a school house in the year 1818 on the turnpike just below the residence of Luther Raymond.”

Although the Raymond house was located on the east side of Chestnut Street at number 954, it is almost certain that this school was located on the southwesterly corner of Boylston and Chestnut.

The Upper Falls School District

In the following year, 1819, the only other recorded scholastic activity in Newton was construction of a new school for the “north west” district. Meanwhile, in Upper Falls when Thomas Handasyd Perkins and his brother James erected their large Elliot Manufacturing Company plant in 1823 at the upper dam on Elliot Street, the center of population dramatically shifted again. At this point the residents and mill owners felt that the village was now of sufficient size and financially strong enough to establish its own school district. Indeed, all of this activity brought a further increase in the village’s school population so that in 1824 the town was obliged to create a special school District for the village of Newton Upper Falls. This was very important since it gave the village representation on the town School Committee as well as the power to employ its own teachers and manage its own school. Only two villages in Newton would have village schools: Newton Lower Falls in 1790 and Upper Falls in 1824.

The new village school committee immediately recommended establishing a school in a more central location in the village. Mr. Pettee, aware of the influence of the increased business activity which in turn brought a further increase in the local school population adds this:

“This large increase in business…made it necessary to have still further school accommodations; consequently the schoolhouse near the turnpike was moved southerly in 1827, to the spot now occupied by the Postoffice building, and sufficiently enlarged to accommodate two schools.”

The postofflce building referred to above is the old wooden (now brick-faced.) block still standing at the junction of Chestnut and Ellis streets opposite the Baptist church.

The new school was divided into two sections in order to operate with a more advanced curriculum than the ordinary district school. This would require the services of two teachers (the first such school in Newton) and no doubt was the nearest: approach to a graded school at the time. Again we are fortunate to have the recorded remarks of a former pupil of this school, John Winslow, the son of an Upper Falls mill worker who begins; “As I was born in 1825 I presume my school career commenced about 183l…” He goes on to describe the school and how it operated.

“It was divided in two parts, known as the ‘Great Part’ and the ‘Little Part’. It was a modest building one story high, and as near as I can remember about 50 or 60 feet long by about 35 feet wide. The easterly end was the little part and the westerly end the great part…. The principal studies in the ‘Great Part’ were Reading, Spelling, Writing, Geography, Arithmetic and Grammar, though there was occasionally an ambitious class in Elementary astronomy. Algebra and Comstock’s Natural Philosophy. There was once in my time a class in ‘Watts’ on the Mind., ‘ when mental processes were calmly considered and closely scanned. I think one of the winter teachers taught the beginnings of Geometry…There was a small orrery operated by a crank, and used to illustrate the Planetary Universe.”

There seemed to have been special emphasis placed on the learning of proper spelling and Mr. Winslow makes a point of this,

“The spelling schools were very interesting as well as instructive and amusing. We generally had them in the evening, though sometimes Saturday afternoons, and would of course, choose sides, the best spellers getting the first calls. It was a circumstance not to be forgotten, that a necessary arrangement was that the boys and girls would sit together, and doubtless some of them had spells long to be remembered.”

One can imagine that George Pettee was quite irked when he found that, although he lived rather close to this “new” and attractive school, neither he nor his brothers and sisters would be able to attend there because the boundaries of the Upper Falls village school district set up in 1824 were so tightly drawn. They ran from the river at the foot of Boylston Street to the top of the hill, then southward along the ridge through the area where the present Emerson School building now stands and continuing southerly to meet the river again. So close was this line set that we find that the family of Otis Pettee, Sr. residing in their home on Elliot Street (now the Stone Institute) was not included in the Upper Falls Village District, and therefore the Pettee children as well as others in the area were forced to attend the Upper Falls District School on Elliot Street;, three-quarters of a mile away, George Pettee, son of Otis, did not like this arrangement and voiced his complaint:

“The division line between school districts located me in a section of territory that provided school privileges near what is known as Crafts Corner, or in the old ‘Cook School House’, three-quarters of a mile from my home. So you will observe, that while I lived within five minutes walk from the schoolhouse in my native village I was obliged to go quite a distance into the suburbs for my schooling, oftentimes wading through deep snow, for the luxury of snow ploughs was not known for our public streets.”

From 1811 to the 1830s this Upper Falls District School was essentially a rural school serving the easterly side of the village proper, together with the sparsely settled northern and southern perimeters. While later he will voice a great deal of respect for the school it was not a particularly happy environment for George at the beginning as he indicates here:

“Notwithstanding our large territory we only had from sixty to seventy pupils and these ranged from five to eighteen years of age, of both sexes, and all under the direction of one master, with no assistant, while the Upper Falls (Village) District, with only one-sixth as much territory, furnished, nearly twice that number, and had two schools in one building, it being the only double schoolhouse in the town at that time…. The Upper Falls (Village) District was densely settled by those engaged in mechanical pursuits, while the district I belonged in was largely agricultural and sparsely settled, so you will readily understand, there were decidedly different characteristics or methods existing among the scholars of the two schools. In the Falls school the boys were in more intimate relation with each other than it was possible for the scholars of my school to enjoy. For they lived quite near the schoolhouse and could be in conference at any time they choose out of school hours. They gathered at the same groceries and post office doors, and used the same river and pond for skating, bathing and fishing; athletic games were in order at all proper times. They had the advantage of attending lyceums and lectures, and gaining practical ideas from men of intelligence and experience in the shops and factories. They naturally acquired the habit of clothing their thoughts with acceptable language while standing on their feet during debate, for they formed into clubs for that purpose. You will keep in mind that the town had no high school at that time, and young men eighteen years of age were often seen in the common district school. But the children in the southwest district, at the dismissal of school, wended their way across vacant fields and over unfrequented roads to their home, not to meet until the following session of school, and, at the close of the term, separated, to meet only by chance until the reopening of school at the close of vacation.”

Eighteenth Century School Life: Discipline, Curriculum, and Examinations

George Pettee refers above to the “young men eighteen years of age…often seen in the common district school”, there being no high school in the town at that time. At this age they were apt to create trouble that would call for some disciplinary action on the part of the schoolmaster. He later writes of one such incident that took place during his attendance at the school.

“When I was quite small, one of the larger boys offended against some rule of the school and the master gave him the choice to either ask forgiveness or take a flogging. I don’t remember the preliminary details that culminated in the final settlement of the affair. However, one afternoon the master produced a large bag containing some heavy articles, which he placed on his desk. The regular routine of the school continued till about one hour before closing time. He then ordered all the books into the desks, and crowded the scholars into the two rows of back seats. Closing all the window shutters but one, which made the room quilt dark, he removed from the bag a hammer, some nails, an ox-chain, a couple of iron staples, a rawhide and sundry other articles. He proceeded to nail the windows down, then passing one staple through a link in the chain he drove it into one side of the door frame followed by the other into the opposite side. Stretching the chain across the door he secured it to the staple with a padlock and put the key in his pocket. This elaborate preparation over, he put his watch into his desk, removed his coat and, armed with his cowhide, ordered Dana (that was the boy’s name, who was as tall as the master) into the floor, or arena of the amphitheatre the schoolroom now resembled. The two rows of scholars, as onlookers, were to witness the struggle of the master for supremacy of the school.

Dana hesitated for a moment.

‘Are you coming or shall I come after you?’

Dana walked slowly down the alley to the floor, and was told to take off his frock and jacket, which he did.. After some explanatory remarks by the master, he told the boy he still had the choice of asking forgiveness or receive his punishment – and he could have just one minute to determine the question. Dana wavered for an instant, but it could hardly have been through fear, for he had ever exhibited the most stubborn pluck and stoic indifference to pain on former occasions when receiving punishment. Whether the suppressed sobs of the larger girls or the audible wailing of the smaller children influenced him or not, certain it is he accepted the compassionate alternative and asked forgiveness of the master and the school; and from the sunny side of the house he was tearfully forgiven.

Thus quietly ended what at first foreboded a fierce tussle, For it was whispered that Dana’s stout friends among the boys of the school would rush to his rescue if the master pressed him too closely. And the consequences might have been fearful, locked in as we were, for a hundred books could have been hurled at the master in as many seconds. However, it is not my province to suggest what might have happened. The door was unchained, the scholars returned to their seats, the nails withdrawn from the windows, the shutters opened – dispelling the somber shades that had lent a deeper impressiveness to the scene. After a few admonitory words from the master, school was dismissed and we all breathed more freely.

Disobedience was more or less prevalent during each term, and reformatory treatment by various methods was also common.”

But there were many days, as George will tell us, when school was conducted without incident.

“The curriculum of the school was limited to arithmetic, geography, reading, writing and spelling, as a general rule, and the scholars were graded into classes known as the first, second and third for each branch of study, except grammar and the history of the United States which was taken by the first class only. All classes recited while standing in line on the open floor, but we were startled at one time by a grand innovation to the rule, by the master allowing the first class to remain in their seats during some of their recitations. We used goose quills for writing, and the master with his pen knife during that exercise was busily occupied repairing pens and giving instructions, after his own method, in that department.

As a general rule we had but little divertissement during school hours; no music, singing, marching or recreative exercises.”

But there came one enjoyable day in the Spring – “examination day.”

“At the close of the winter term we had a grand public examination before the School Committee, and usually a large gathering of spectators who occupied one side of the schoolroom made vacant by all the scholars closely sitting on the other. The physical preparations were exhaustive, whether the mental were or not, for the woods were ransacked for evergreens by the boys for decorating the room, and the girls came fortified with soap, sand and scrubbing brushes for scouring the benches and for general cleaning up of the schoolroom. But money was scarce, so house cleaners could not be hired” and the girls were determined to have a clean room while entertaining their friends, and the boys cooperated by assisting in every way they could to make the occasion attractive.”

And there was pride in having more than a clean classroom:

“We had nothing to do with written examinations for promotion or otherwise. The Committee, however, questioned us at times, when visiting the school and at its closing exercises. And we were always glad to learn from them that we had made satisfactory improvement, a commendation often bestowed upon us, and the Southwest School ranked with the first in town.”

Although he called it a “rookery” George pays tribute to the graduates of his school:

“Only the favored few secured a polished education, for rich fathers were not plenty, while well-to-do or forehanded farmers or mechanics, constituted our wealthiest families. But we had good material grazing on those rocky hillsides for knowledge, for men, eminently successful in their own undertakings and those holding important positions of trust, are still living, who received their earliest dozen years of schooling in the diminutive ‘Cook Schoolhouse’, of whom I will refer only to the Hon. J.F.C. Hyde, first Mayor of the city of Newton, by whose side I had the pleasure of sitting for a number of winter terms, and Otis Pettee, Esq., (his brother) first Alderman of Ward Five.”

NOTE: this was written in 1883.

As for George, following his graduation from the “Cook School house”, he went on to attend several terms in Marshall Rice’s private school at Newton Centre and then later at Wilbraham Academy from which he graduated with honors.

In those days when boys were needed on the farm or in the mill to help support what were usually large families, it was a struggle for those who wanted to get a proper education. John Winslow was well aware of this as 11 out of 14 children in his family were all attending the village school at one time. He tells how it was accomplished:

“It was not an unusual thing for some of the boys, whose means were nothing, but whose purpose to gain some education was undaunted., to go from the school at four o’clock p.m., to the shop or mill and there work until one-half past seven in the evening, and thus make it possible to attend school at all. Surely with such boys, life was real and life was earnest In those days school opened at nine in the morning, recess at twelve until one, then it continued until four o’clock. The custom was to have a vacation in the term of one day every other Saturday.”

After the village school, John Winslow managed to attend private school a few months at a time, first in the “Vestry” on High Street, Upper Falls operated by Ebenezer Woodward, a former public school teacher. He later spent six months as a pupil of Marshall Rice in his private school for boys at Newton Centre and in 1843 attended the Holliston (Massachusetts) Academy taught by Gardner Rice, brother of Marshall.

He then prepared for college at Phillips Academy, spent two years at Brown University and graduated from Harvard Law School in 1850. After sharing a law office with his brother David in Brooklyn, New York he was elected to the office of District Attorney of Brooklyn. He looked back with fond memories over the road he had traveled.

“Since I left the old schoolhouse I have seen something of study elsewhere – in Academy, in University, and in Law School. In all these there were appliances and facilities not, of course, to be found in ‘the modest Upper Falls Village School. But, upon looking back upon the early school days, I am disposed to draw the lesson that after all, the real key to success is study, is not chiefly in what is called modern advantages, but mainly to earnest work and application.

That a fair share of love of study prevailed in the old village school, I here declare if the real truth could be known I venture to believe that many commendable and courageous cases of self-denial for the sake of education could be cited from the annals of Newton Upper Falls.”

This was certainly a tribute in part to the residents of Upper Falls who were willing to financially support a school that would provide such a strong basic education. In 1824 when the Upper Falls school district was formed, Newton was spending but $l300 for the entire number of districts then in operation. Perhaps realizing that this small amount would. be difficult to administer, the town in May, 1821 (when the apportionment was but $1100) voted that “the several school districts be allowed and empowered to apply their proportion of school money for schooling as they may think best, and manage their schools in their own way.” This vote was affirmed in 1823.

The Newton Upper Falls school district’s administration was handled by the “prudential committee-man” and “he was elected by the people of the school district. His business was to hire the teachers, replenish the woodpile and look after the schoolhouse generally.”

A Second Generation of School Buildings

By the 1830s there were nine schools in town including one each at Newton Corner, Nonantum and West Newton. There were actually three at Newton Centre with one near the church, one at Oak Hill and the third on what is now Hammond Street near Commonwealth Avenue. There was the village school at Lower Falls, one in the village of Upper Falls and finally the 1811 district school at “Cook’s Corner” (Upper Falls).

A short time after George Pettee left this latter school it was abandoned for two reasons, the first of which is contained in this article appearing in the TOWN CRIER‘s edition of March 3, 1905:

“This schoolhouse…became dilapidated, so much so that it was almost impossible to heat it, and the schoolmaster said he would not teach another year unless he had a new schoolhouse so in 1836 or 7 (actually 1846) a new two-story edifice was built on the opposite side of Elliot Street and the old sold, and moved away to a lot on Mechanic Street where it now stands as a dwelling house.”

Whose house it became is not known. However, the real reason for the abandonment of the old 1811 school was that it could not accommodate the increased number of students, the result of a large number of workers and their families moving into the area. The Pettee Machine Works had begun operations in the vicinity in 1831 and its expanding business contributed to a large increase in population. Otis Pettee, Jr. later explained how this affected the school:

“This work called a large number of families, most of which were located in southwest (old Upper Falls) district, where their children attended school…. in order to accommodate this increase of scholars, a new commodious house with two stories was built opposite the old, on land given by Mr. Winchester.”

Newton records show that in 1846 Amasa Winchester gave land located on Elliot Street next to the present MBTA tracks, in front of the Boston Edison Company’s property, to the city. While the school has long since disappeared, the lot remains open since Mr. Winchester’s will stipulated that the land. “shall be forever used for the purpose of education.”

It would appear from Smith’s history that schools of two stories in height were not built in Newton until March 15, 1852 when the town voted “that the School Districts of this town be and hereby are abolished.” We quote from a report of a task committee on March 29th of that year:

“Your committee, in view of the rapidly increasing population of the town, and consequent growing demand for school-houses, consider the erection of one story school-houses as injudicious and unprofitable. They therefore recommend the erection of two school-houses,’ each two stories high, sufficiently large to accommodate a grammar school upon one floor.”

However, there is evidence that the two village school districts, Upper and Lower Falls, had two-story schools several years earlier. We do not know whether the 1827 two-room school on Chestnut Street was demolished or moved again, possibly to become a residence, but we do know that its replacement was a two-story school building and, though later moved nearer the street, is still standing today at 1028 Chestnut Street occupied by stores and apartments.

Despite its short life this school was abandoned in 1855 (one record says 1853) when its replacement was built on High Street at the time the single graded system took effect in Newton. Only a few years after the abandonment of the 1846 school on Chestnut Street we might question the memory of Otis Pettee Jr. a bit when he later wrote:

“The old school by the post Office, having been out of repair and insufficient in size, a new house was built with two stories and all modern improvements on what was known as the frog pond lot….The village house was sold at auction to Mr. Marcy, for groceries and dry goods stores.”

Coincidentally, the 1846 Upper Falls School on Elliot Street was abandoned about 1855 or near the time the single graded system was inaugurated. Otis Pettee Jr. tells us it was “sold to Mr. Davis C. Mills and removed to the village, and is now occupied by Mr. Cady as a tin shop, etc.” The building, identical to the one built on Chestnut Street, was relocated on the southwest corner of Elliot and Chestnut Streets and was the predecessor of Hagerty’s Meat Market which a few may remember. It was later razed to make way for the modern condominiums now occupying the site. Incidentally, in 1855, Chestnut Street was extended from Elliot to the Depot, the railroad having arrived in the village in 1852.

The new school system established in 1855 resulted in a single new school being built that year on High Street to serve Upper Falls as previously noted. It is described as having four rooms that housed three primary classes and six grammar grades. It was called Prospect School, taking the name of the hill upon which it was located. In a very short time this school proved to be inadequate in size. Due to an increased number of students, Elliot Hall and the upstairs room of the fire station on High Street were pressed into service for school purposes. A news item of February 2, 1867 indicates that the “School Committee (District 2) had rented room in Elliot Hall for Sub-Primary for 70 children.”

That same year the school, now labeled Prospect #1, was moved back on its lot to make way for a new school to be called Prospect #2. Prospect #1 remained in service accommodating the first and second primary grades and later a kindergarten. A report in the Newton Journal concerning the dedication ceremonies of the new school completed in 1869 included this statement: “As there are about 280 scholars in this section of town, the old schoolhouse, which had been removed to the rear and fitted up, will still be used for two primary classes of the school.”

A previous vote of a town meeting in March 1867 had authorized the expenditure of $l2,000 to purchase additional land on which to locate this older Prospect #1 school.

The new school, Prospect #2, built in 1869 was a four room building

The rooms were large and the building featured wide corridors and stairways and included teacher’s offices.

A large auditorium with a stage was located on the third floor and was used as a village hall for meetings, dances, dramatics and social events. The school house contained the primary, third grade and the fourth to ninth grammar classes with two classes to each teacher in each room.

As early as March 1838, the town had appointed a committee to consider “one or more free High Schools in Newton.” In May their report was ordered to be printed and a copy provided to every family in the town. Historian Smith comments, “But the time evidently’ had not yet come.” The state had drawn up certain rules governing the obligation of towns with over 4000 inhabitants to establish a high school. The rules involved various matters including school districts, types of studies and length of terms. These rules and the distance to the location of a new school had deterred Newton from complying with the law, and the committee’s report reconsidering the situation include the following:

“Several towns so situated, including Newton, have at different times petitioned the Legislature to be released from the obligation to maintain High School instruction. To remedy the evils complained of by these towns, the Legislature passed an act in 1848 permitting towns in which High School instruction is required but containing less than 8,000 inhabitants, to establish in said districts, as the School committee may determine, two or more schools for short terms, but which, taken together, shall be equal to twelve months. It is therefore manifestly competent for the town to establish one school embracing High School studies for the term of ten months, or a larger number of schools having such studies for an aggregate period of twelve months, and to embrace within these schools the common studies usually assigned to Grammar Schools.”

As a result of the above report the town voted to build two new schoolhouses and they were immediately erected, one at Newton Centre and the other at Newtonville. We quote from Smith’s history:

“The committee determined to establish the first High School at Newton Centre, and built the house with reference to that end. Mr. John W. Hunt, formerly teacher at Plymouth, Mass. was the first instructor….The arrangement proved to be a success….The plan, however, was also a stepping-stone to something better. And in 1859 a resolution was adopted at the town meeting, March 7, recommending the establishment of a pure High School, to be located in Newtonville, ‘on a lot of land next to the entrance to Mr. Claflin’s ground on Walnut Street.’ The school was established as an ‘experiment, which they will continue to watch anxiously yet hopefully, leaving the results to speak for themselves.’ it commenced with seventy-five pupils, all of whom were over fifteen years of age, under the instruction of two teachers…Within ten years the school building, supposed at first sufficient to provide amply for the wants of the far future, was greatly enlarged. The force of teachers was doubled, and the pupils numbered nearly one hundred and fifty….”

However, although the building was erected in 1859 a superintendent was not appointed until 1870. Also, high school classes continued to be conducted in other schools as indicated by this action taken by the School Committee at the time of the dedication of the new Prospect #2 school at Upper Falls in 1869:

“It should be stated that within a short time a high school department has been established in this school, on vote of the School Committee, where branches of education similar to those at the High School at Newtonville are taught under the supervision of Mr. Wade, the principal.”

This may be in part a tribute to Mr. Wade who became known as an outstanding educator, among other achievements, and so well known in public life that after his death his wife returned to the village and offered to put a clock in the cupola of the Prospect School if the name was changed to “Wade School”.” Her wish was granted by the town as recorded in this news item of October 6, 1893:

“The aldermen have very appropriately regarded the wish of the people of Newton Upper Falls and of the school board in renaming the Prospect schoolhouse in that village in honor of the late Hon. Levi C. Wade. The deceased was not only the first master of the school, but was a prominent Newtonian and was always public spirited and interested in the welfare of the city in which he rose from obscurity as a school master to the distinguished public man and able head of one of the large railway systems of America.”

Unfortunately, the clock was never installed in the cupola because of a weakness in the structure. (See biography of Levi C. Wade)

However, in order to complete the story of this remarkable dynasty of the Upper Falls schools we return to follow the career of this school. It seems incredible that the village was expanding so rapidly that only l2 years after the dedication of Prospect #2 (Wade) School the old bug-a-boo of overcrowding cropped up again. We read from a news account of June 11, 1881:

“The overcrowded conditions of the 1st class of the Prospect School has necessitated the forming of an additional class which occupies Quinobequin Hall, in the old Schoolhouse, with Miss Josie N. Hopkins as teacher.”

Quinobequin Hall occupied the second floor of the 1846 school on Chestnut Street that was abandoned in 1855.

In 1880 graduates of the Prospect grammar schools decided to have annual reunions of the previous classes as indicated by this news item:

SECOND ANNUAL REUNION OF THE GRADUATES OF THE PROSPECT GRAMMAR SCHOOL

“One year ago a reunion of the past pupils of the Prospect (formerly Elliot) school, was held in the schoolhouse hall, on which occasion it was filled to overflowing. From the interest manifested by those attending it was concluded to hold these gatherings annually, and the second assemblage was held on Monday evening, Jan. 17, (188l).”

Note that, at least far a brief time, the Prospect #2 School must have borne that familiar name of Elliot. These graduates took their reunions seriously and invitations to them were quite elaborate, very formal, many with deckled edges and engraved printing. Available newspaper clippings indicate that at least l5 reunions were held. Two of the addresses given at these gatherings, one by John Winslow in 1882 and the other by George Pettee in 188g, have survived and are quoted at various points throughout this book. These affairs seem to have taken place during the heyday of school activities in the village. Perhaps many believed in those days that nine grades of grammar school were sufficient for their education and this feeling tended to create closer ties with the only school they would ever attend.

By 1903 the days of the Wade School were drawing to a close. Built in 1869 at a cost of $23,280.75 to the city, it was shown on a school valuation report of 1870 to have a value of $32,000, including furniture and land. The value of the Primary schoolhouse (Prospect #1) also including furniture and land, was shown as $7500. A lot listed as school department land in Upper Falls was valued at $1400. This is presumed to be the present “open” lot on Elliot Street, in front of the Boston Edison Company’s property.

In 1904 the Wade School observed its last graduation with the ceremonies held in the Hyde School in Newton Highlands since the old school was being moved to the rear of the school property, a procedure that its predecessor, Prospect #1 had experienced 35 years before. By now Prospect #1 had outlived its usefulness and was sold to Joseph Barney who moved it across Pettee Street near the corner of Thurston Road. There it was used for all types of public gatherings.

Wade School was moved onto the site vacated by Prospect #1 and its use as a school was discontinued, although it was still the property of the City of Newton. The Newton Upper Falls Improvement Society had a rent-free lease and sub-let it to David Murdock of Needham. He operated it as a motion picture theatre until sometime in the late 1920s when the competition and cost of sound pictures made its operation too costly. The building was finally razed to provide more school play area.

The Emerson School

In 1904 a brick school was built at a cost of $92,408 on a site in front of the Wade School. It was named the Ralph Waldo Emerson School to honor that famous American essayist, philosopher and poet. When Emerson returned from Europe in 1833 he settled down with his mother in the old Bethuel Allen House on Woodward Street (since demolished), a quiet old farmhouse a half-mile from the village. The lovely rural scenery surrounding the village of Upper Falls was for a long time the delight of Mr. Emerson. Since lyceums, a system of public lectures, had just been introduced to America from England, and conducted in Upper Falls schools during Mr. Emerson’s residence here, he no doubt addressed many of these lectures. It was appropriate that a school here should bear his name.

The building housed all classes from kindergarten to ninth grade. After the introduction of the junior high system, it contained a kindergarten and six grades. It also housed a branch reading-room of the Newton Public Library and, for many years, a third floor auditorium. In 1955 an addition to the Emerson School provided a gymnasium, an all-purpose room, a kitchen and one additional classroom at a cost of $335,79l.

Nothing would please us more than to say that the Emerson School or a successor still serves the old village but this is not the fact. Decline in school enrollments in the 1970s and 1980s made school closings necessary in order to cut costs. In some cases political pressures dictated the choice of which schools would be closed. Smaller and less affluent villages became vulnerable, and although it did not fit the criteria, Emerson became the victim of political maneuvering. In the last eight minutes of a memorable school committee meeting assembled to discuss the closing of other schools, its name was suddenly proposed and the deed was done. Thus, in 1979, after more than a century and a half the influence of one of the city’s pioneer schools was abruptly removed from the village.

Fortunately, the Emerson School building remains, ironically now standing in the village’s historic district and housing a number of condominiums. The 1955 addition now includes a day care center, a senior citizen room and gymnasium-hall, etc. Unfortunately, the city has also removed the branch library that had served the village for a century.

Nineteenth Century Teachers Remembered

It is extraordinary that the names of the village school teachers from 1855 to 1979 exist. John Winslow supplies us with some of those who taught here in the 1830s!:

“The first teacher I remember was Elizabeth Bixby….She was the daughter of Deacon Bixby, a leader in the Baptist Church nearby….The custom was to have a lady teacher in the summer and the other kind in the winter. Among the summer teachers I remember Miss Esther Plimpton, Miss Durant, Miss Palmer of Oak Hill and my oldest sister, Clarissa. I think they were all faithful and more than earned their wages….Among the winter teachers, I remember old Mr. Cushman, Mr. Barrows, Eben Woodward, Mr. Frost, Mr. Merrill, Mr. Hackett, Mr. Plimpton, Mr. Woodbury and Mr. Lord. I have heard there was a Mr. Harding before any of the above, but I never saw him…Mr. Asahel Plimpton, who had charge of the ‘Great Part’ one winter, was a successful teacher and a life-long resident of Upper Falls. He became a physician and has practiced many years in Shirley.”

For the record we give here the early schoolmasters of the first Prospect School:

| D.M. Hoyt H.P. Andrews C.N. Dunsmore James T. Claflin T.H. Mudge P.C. Porter ??? Hill | 1855 1858-l859 1855-1858 1858-186l 1857 1861-1863 1863-1868 |

After Levi C. Wade as the first master of Prospect #2 (later the Wade) School, came the following schoolmasters:

| D.C. Farnham C.E. Hussey ??? Harwood Chas. G. Wetherbee Walter C. (Jack) Frost C.E. Gaffney | 1873-1876 1883-1892 1876-1880 1892-1902 1880-1883 1902-1906 |

C.E. Gaffney had. become master of the old. Wade School in 1902 and he continued. as master at Emerson until 1906. Following him were:

| Frederick (‘Pa”) Hodge Clarence Churchill Joseph Randall Arthur W. Howard Raymond Cook Joseph Gattuso David Whiting Catherine Harney Donald Welch Cameron L. Larson Nanette Cochran | 1906-1932 1932-1938 1938-1948 1949-1950 1950-1956 (promoted. to asst. to Supt. of Schools) 1956-1964 1964-1967 1967-1968 (Acting Principal) 1968-1972 1972-1976 1976-1979 |

Giving Names to Forgotten Faces of the Emerson School

- “Pa” Hodge

- Helen Preble

- Elizabeth Dugan

- Thomas Motherway

- Daniel Valente

- John Balkus

- John “Pat” Mahoney

- Joseph “Pic” Picariello

- Bartloof “bbarley” Kosrofian

- John Temperley

- Miss “Kitty” Sullivan

- Alice Crowley

- Cecelia Roman

- Mary MacKenna

- Walter Billings

- Albert Mordo

- Ulderico Schiavone

- John “Shawk” Shaughnessy

- Edward Osborne

Private Schooling

It might be well to remind our readers at this point that Newton Upper Falls had one of the earliest private schools in Newton. Sometime during the 1840s Ebenezer Woodward, a member of that early pioneer family in Upper Falls, conducted such a school on High Street. He was a remarkable man. Born about 1812 he entered the old southwest school at the age of five, and 14 years later he was master of the same school. George Pettee, who had been one of his pupils, stated later, “the two winters he taught were unusually profitable to the children”. A year or two later, he was teaching in the old village school near the Baptist Church. John Winslow, one of his pupils there, remarked in his reunion address:

“I have mentioned Mr. Eben Woodward as one of our teachers in the early days. He had charge of the ‘Great Part’ in the winter of 1835. I distinctly remember the year because it was the winter of the great fire in New York, which was the subject of conversation in the school. Mr. Woodward afterward kept a private school on the hill in a building known as the ‘vestry’, which was afterward used as a tin shop. Most of this generation doubtless remember him later as a teacher in a flourishing private school at what used to be called Angier’s Corner, afterwards Newton Corner, now Newton. Mr. Woodward – in later years known as Deacon Woodward – was a splendid man – in a human sense, – a model man.”

The location of the old tin shop in Upper Falls where Mr. Woodward had his private school was on the southwest corner of High and Winter Streets, owned by Colin Cady. It was destroyed by fire in July, 1869. Deacon Woodward continued to be identified with the village. His property, at the top of Boylston Hill, later known as Pierce’s Woods, was conveyed to Mr. Pierce after the Deacon’s death in 1880.

We have attempted to give the reader an extensive review of the history of education in the schools of old Upper Falls Village. It was not easy for a boy in a mill village to acquire an education. Mill workers’ wages were low and many a boy went to work in the factory at an early age in order to augment the family income. A similar situation prevailed even outside of the industrial areas of Newton where farming was the predominant means of gaining a livelihood. Planting, harvesting and general chores took precedence over education, and absenteeism was a major problem in the schools. In 1845, Newton had a rate of absenteeism over 43%, the highest among Middlesex County’s 48 schools. Surprisingly, there were laws in the town regarding the education of children working in the mills, such as one “that required every manufacturer who employs children to dismiss them from work, at least three months of each and every year, to attend school,” We have seen no evidence that this law was applied in Upper Falls. We did find that not every boy was anxious to leave school for the mill. John Winslow, as previously indicated was one of 10 children of millworker Eleazer Winslow. We repeat here some of his words describing his determination and that of most of his schoolmates to get an education:

“It was not an unusual thing for some of the boys, whose means were nothing, but whose purpose to gain some education was undaunted to go from school at four o’clock p.m. to the shop or mill and there work until one-half past seven in the evening, and thus make it possible to attend. school at all. Surely with such boys, life was real and life was earnest…”

The slow upward progress of the Newton school system after the merger of 11 individual school districts into one, single, graded system is well documented. The launching of a successful high school program became the chief obstacle. We have read earlier that the high school opened at Newtonville in 1859 with 75 pupils in attendance and that ten years later, in 1869, the pupils numbered nearly one hundred fifty. Yet we also read from the same source that the number of graduates from the school were very few for quite a number of years after its opening. Records show that the first (four year) graduating class consisted of just four pupils, all girls. Significantly, in 1866 during the Civil War the graduating class again consisted of all girls, nine in number. During the following years, the number of graduates never exceeded 20 and in 1873, the last year before Newton became a city, there were only 18 graduates, eleven boys and seven girls. That same year, three year courses were offered and there were 20 graduates from the first class, twelve boys and eight girls.

Although the achievements of the high school initially were few, the results of its efforts began to take on lustre by the end of the century when the population of the city was increasing rapidly.

After two centuries of trial and error, Newton began to receive honors for its scholastic endeavors – a Diploma of Merit from the World’s Exposition in Vienna and later, similar honors at the Paris Exposition. By 1914 the school population numbered 7519 students (574 Kindergarten, 5021 Grades and 1924 High School). Superintendent Frank Spaulding announced, “No other city and only one town in the state has invested in its school plant; as much per pupil as had the city of Newton”.